-

As a potential n-type metal oxide semiconductor material, ZnO has been employed in various fields, such as solar cells1, photocatalysis2, and sensors3, owing to its unique properties4. Nanostructured/nanoscale ZnO often exhibits enhanced device performance compared with its bulk counterparts owing to its increased specific surface area5. However, conventional nanomaterial synthesis techniques are generally non-site-specific, making patterning critical for the fabrication of functional devices. Unfortunately, the post-growth patterning method, which involves separate growth and assembly processes, is cumbersome and extremely time-consuming6. Alternatively, solution direct-patterning (SDP) techniques based on liquid-phase precursors, such as screen printing7 and inkjet printing8, have been developed to directly print the precursors of these materials9–11. However, these methods face significant challenges, including stringent and precise rheological property requirements for the precursor and limited precision owing to the constraints imposed by the nozzles and templates, which restrict the flexibility in regulating precursor components and impede the capability of high-density integration of devices. Recently, laser direct writing (LDW), which has attracted considerable attention owing to its advantages of being a non-contact, cost-effective, and spatially confined reaction12–15, has been successfully applied in preparing patterned structures in various materials, including metals16,17, metal oxides18,19, and carbon-based materials20. In addition, by modifying the composition of the precursor solution, using LDW could enable the heterogeneous processing of multiple materials21. These works illustrate the exceptional benefits of LDW in fabricating functional materials and devices, thus eliminating the need for vacuum and high-temperature annealing treatments and laying the foundation for the fabrication of complex electronic devices by LDW.

Although ZnO micropatterns have been successfully fabricated using LDW technology18,19,22-24, utilizing continuous/nanosecond lasers in these studies resulted in the generation of heat-affected zones, which significantly constrained the precision of the LDW products. In addition, for substrates and precursors transparent to the laser processing wavelength, a pre-prepared light-absorbing layer is necessary to enhance the light-absorption efficiency and facilitate the desired reaction, increasing the cost and complexity of processing and preventing the integration of functional devices on dielectric substrates. The femtosecond laser direct writing (FsLDW) technique has attracted considerable interest because of the short pulse widths of the femtosecond laser, which can induce a multiphoton non-linear absorption effect and significantly reduce the heat diffusion length compared with continuous-wave (CW) or nanosecond lasers, thus enabling the preparation of silver micropatterned structures with a sub-diffraction linewidth25. Herein, a novel approach is demonstrated by combining the FsLDW technique with the sol–gel method to realize the single-step synthesis of patterned ZnO nanomaterials. When a tightly focused near-infrared femtosecond laser was applied to the precursor, a multiphoton absorption effect occurred inside a tiny voxel owing to the ultrahigh peak energy of the femtosecond laser, which initiated the synthesis of ZnO nanomaterials. Owing to the non-linear absorption effect of femtosecond lasers, this method negates the necessity for a laser-absorbing layer, thus offering significant advantages for preparing and integrating practical ZnO functional nanomaterials26–28. This method also enables the direct fabrication of customizable 2D micropatterns without masks on various substrates, including flexible substrates, in an atmospheric environment. The minimum linewidth of the patterned ZnO layer was less than 1 μm. Furthermore, by leveraging the regulatory effect of glycerol additives on grain growth, we reduced the grain size and effectively addressed the issue of discontinuity and non-uniform product formation during FsLDW—critical for the integration of functional devices. Moreover, using this technique, we prepared a series of UV detectors. Owing to the grain-modulating effect of glycerol, the product exhibited a smaller grain size and larger specific surface area, resulting in exceptional photoelectric detection performance, with a switching ratio of 105, responsivity of up to 102 A/W, and an ultralow dark current of less than 10 pA. The dark current is one order of magnitude lower than that of previously reported ZnO UV photodetectors at the same bias voltage29–35—crucial for improving the signal-to-noise ratio and reducing the power consumption of photosensitive detectors. This method can be further extended to fabricate other metal oxide nanomaterials and offers significant potential for high-density multifunctional device integration, including MEMS, optoelectronic devices, catalysis, and energy devices.

-

The preparation of the precursor and fabrication of the micropatterns using FsLDW are illustrated in Fig. 1. The precursor was prepared using the sol–gel method with zinc acetate dihydrate as the zinc source, 2-aminoethanol (MEA) as the stabilizer, 2-methoxyethanol (EGME) as the solvent, and glycerol as the functional additive, as shown in Fig. 1a (see Experimental Methods for more details). The chemical reactions of each component during preparation are shown in Fig. 1b and S1. First, the solvated zinc acetate releases zinc ions, which undergo alcoholysis/hydrolysis with EGME/crystallization water to form Zn-OR and Zn-OH bonds. The alcoholysis/hydrolysis products undergo condensation to form a soluble colloid11,36. In this case, the MEA and acetate groups inhibit alcoholysis/hydrolysis and condensation reactions through coordination with zinc ions to prevent the generation of insoluble precipitates or nanoparticles37,38. The precursor was a transparent pale yellow solution, as shown in Fig. 1a. However, the MEA and acetate group complexes gradually undergo hydrolysis, and the hydrolysis products continue to condense, forming nano/sub-nano colloidal particles. Therefore, precursors should not be stored for long periods.

Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of the precursor solution, consisting of zinc acetate dihydrate, 2-aminoethanol (MEA), 2-methoxyethanol (EGME), and glycerol. b Precursor solution undergoes dissolution, chelation, hydrolysis, and condensation reactions to form sol–gel precursor. c Absorption spectra of precursor solution and solvent; inset: schematic diagram of multiphoton absorption. d Schematic diagram of the synthesis process: spin coating, FsLDW, and development.

The obtained precursor solution was spin-coated onto an oxygen-plasma-treated substrate. This substrate can be made of silicon, flexible polyimide, or soda-lime glass. The spin-coating film thickness obtained by the fluorescence intensity analysis method is approximately 4.3 μm, as shown in Supplementary Movie 1. The oxygen plasma treatment enhances the hydrophilicity of the substrate, thereby facilitating the spin-coating process. A 780 nm Ti:sapphire femtosecond laser (80 MHz, 100 fs) was focused on the precursor film via a high numerical aperture (NA) objective to initiate the synthesis of ZnO nanomaterials (the spot diameter was approximately 700 nm). Fig. 1c shows the UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra of the ZnO sol–gel precursor and EGME solvent. The ZnO precursor showed no significant absorption in the near-infrared region; however, a distinct absorption peak appeared at approximately 272 nm compared to that of the EGME solvent, attributed to the active components of the precursor formed by the hydrolysis and condensation of zinc ions. The soda-lime glass substrate and precursor were almost transparent in the laser processing range, as shown in Fig. 1c and S2. We believe that under the irradiance of a femtosecond laser with a high peak power density, the laser-induced non-linear multiphoton photochemical effect leads to the breakage of the Zn-OR and Zn-OH bonds, accelerates the condensation process, and generates ZnO seed grains. Subsequently, with the accumulation of laser pulse irradiation, the seed crystals gradually grew and eventually formed large grains. Given the low absorption of ZnO in the laser wavelength range and the cold processing characteristics of the femtosecond laser, it is reasonable to conclude that the photochemical effects remain the primary factor.

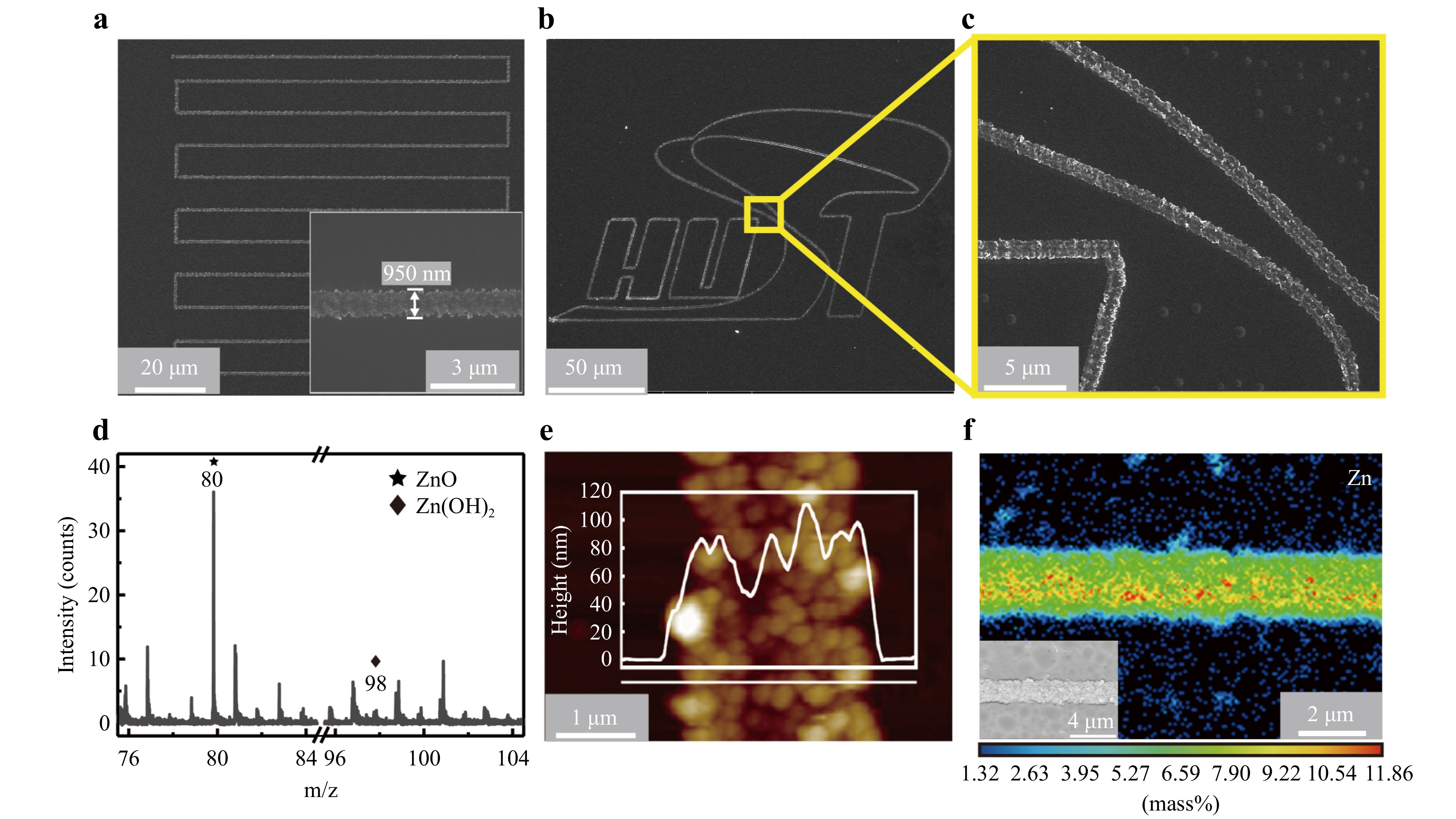

After rinsing the samples with EGME and ethanol, high-precision ZnO nanomaterial micropatterns were obtained. As shown in Fig. 2a–c and Supplementary Movie 2, arbitrary ZnO micropatterns, including bow-shaped lines and logo patterns, were fabricated by controlling the laser beam scanning in a designed pathway through a galvanometer or a two-axis stage based on the pre-loaded patterns. Owing to the minimal light absorption of the soda-lime glass substrate and precursor in the 780 nm spectral range and the ability of ultrashort laser pulses to minimize the heat-affected zone while inducing non-linear multiphoton absorption effects, we can achieve high-precision fabrication of ZnO products. The linewidth could be less than 1 μm, while the thickness is approximately 80 nm, as shown in Fig. 2a, e. Furthermore, we investigated the morphology of the ZnO microstructure under different laser-scanning conditions, as shown in Figure S3. When the laser power was <60 mW, the line width could be decreased to approximately 1 μm at a scanning speed of 10 μm/s. When the scanning speed was larger than 100 μm/s, insufficient laser power made it difficult to fabricate continuous patterns, as shown in Figure S3c. This process does not require masks, vacuum chambers, or laser-absorbing layers (e.g., metallic layers) for heat accumulation. Fig. 2f illustrates the uniform distribution of Zn along the laser-scanning pathway using wavelength-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (WDS) mapping. Furthermore, the “cold processing” feature of femtosecond laser results in negligible thermal accumulation, allowing for the integration of patterned samples onto flexible thermosensitive substrates such as polyimide (as shown in Figure S4) without any significant thermal damage. Therefore, this technology is promising for integrating functional metal oxide devices into flexible electronic devices.

Fig. 2 Characterization of the as-fabricated ZnO patterns. a, b SEM images of the prepared patterned ZnO, including bow lines in a and the school badge “HUST” in b; c Partially enlarged image of the “HUST” pattern; the inset in (a) shows the minimum linewidth of ZnO products; d SIMS characterization results of the product; e AFM characterization results of the product; f WDS images of the obtained ZnO, where the distribution of zinc elements is consistent with the FsLDW product.

To evaluate the chemical composition of the FsLDW products, we prepared a square pattern with dimensions of 0.8 × 0.8 mm and conducted secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) analysis, as shown in Fig. 2d. The results showed that ZnO was the dominant component, with a mass-to-charge ratio of 80, whereas the presence of the intermediate product, zinc hydroxide (mass-to-charge ratio of 98), was negligible. XPS was conducted to further examine the elemental chemical states of the prepared samples (Figure S5). The double peaks in Figure S5a located at the binding energies of ~1022 and ~1045 eV can be ascribed to Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p2/1, respectively39. Notably, for the untreated sample, the binding energy of Zn 2p is slightly higher than that of the sample treated with thermal treatment in an oxygen atmosphere at 350 °C for 2 h. This difference may be due to common defects such as Zn interstitials and vacancies in ZnO40. The O 1s spectrum was deconvoluted into four peaks corresponding to four types of oxygen atoms: lattice oxygen (OL, ~530.5 eV), vacant oxygen or hydroxyl oxygen (Ov, ~532 eV), surface oxygen (Os, ~533 eV), and residual oxygen-containing organic groups on the surface of the product (Op, ~534 eV)39,41. Notably, the sample without the heat treatment had a low concentration of lattice oxygen and contained organic residues, indicating poor quality and crystallinity, which can be effectively remedied through a subsequent thermal treatment, as shown in Figure S5b. The same phenomenon was observed in micro-area X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Figure S6). The XRD spectrum of the sample without thermal treatment displayed no apparent diffraction peaks, indicating an amorphous crystalline state, whereas the (002) characteristic diffraction peak was present in the XRD spectrum after thermal treatment. Owing to instrumental limitations, further increasing the laser power to improve the crystallinity is difficult. However, crystalline ZnO can be achieved directly using a femtosecond laser with a higher output power or pulse energy42.

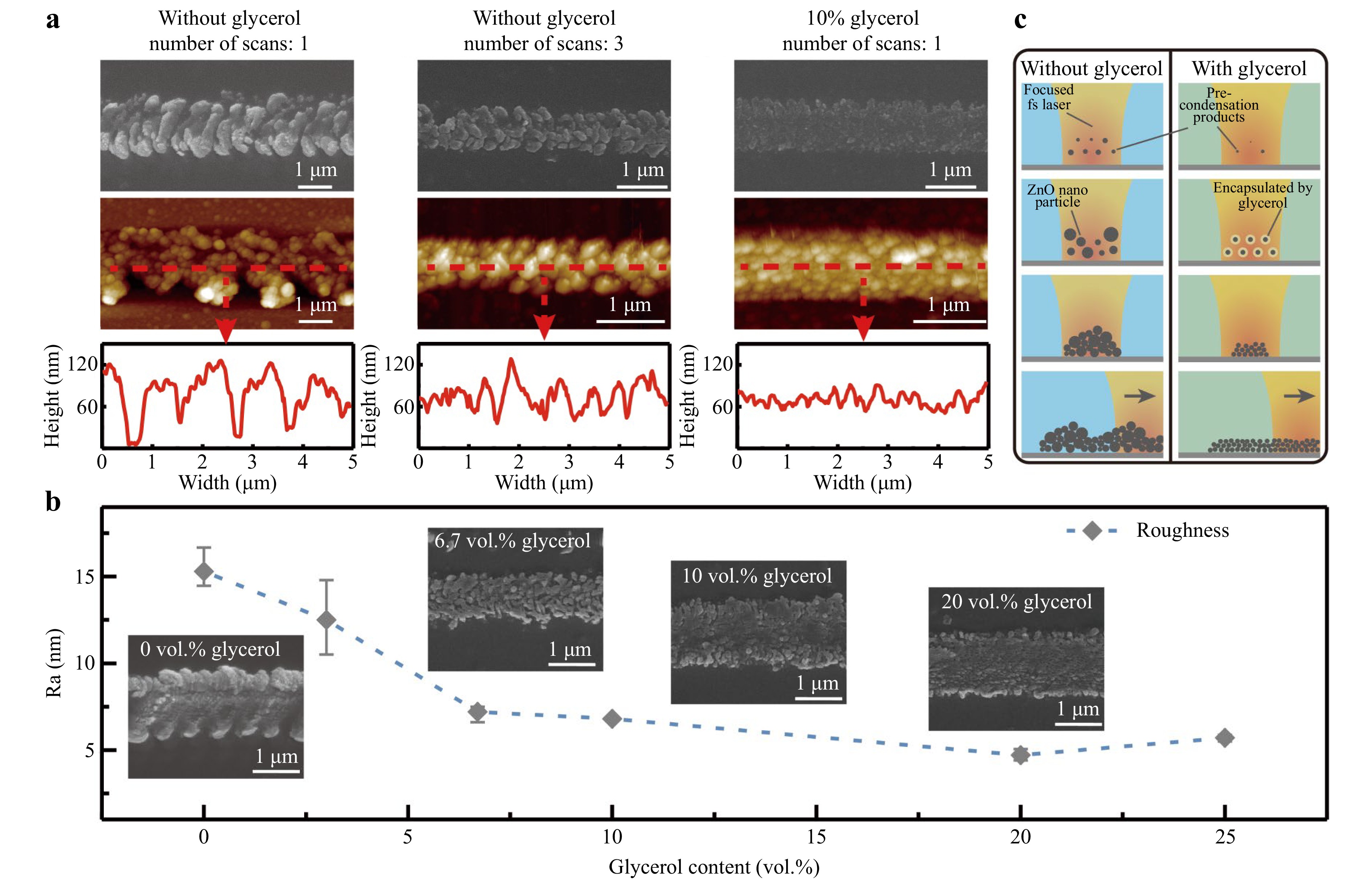

Uniform and continuous products are crucial to achieve stable electrical interconnects. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to characterize product uniformity and continuity. As shown in Fig. 3a, single-time FsLDW resulted in agglomerated, discontinuous, and rough particles (Ra~15 nm). Although the surface morphology improved after three repeated scans along the same path, the particles were still agglomerated with a considerable surface roughness (Ra~12 nm). Polyols have been demonstrated to play critical roles in the synthesis of nanomaterials. As a representative polyol, glycerol has been shown to function as a regulator of ZnO grain growth, preventing uncontrolled grain growth43. Thus, to alleviate agglomeration and discontinuity in the FsLDW process, glycerol was incorporated to modulate grain growth and reduce grain size. As shown in Fig. 3a, by adding 10 vol.% glycerol, the morphology of the FsLDW ZnO products improved considerably while the surface roughness decreased significantly (Ra~7 nm). Fig. 3b shows that the surface roughness decreased with an increasing volume percentage of glycerol added to the precursor solution. When the volume percentage of glycerol increases, the surface roughness of products steadily reduces. Thus, adding glycerol can lead to more homogenous nanoparticles and a denser product morphology when using the FsLDW technique. Furthermore, we analyzed the grain size distribution of the FsLDW ZnO products from precursors without glycerol and with 20% glycerol. Remarkably, with the addition of glycerol, the average grain size of the product decreased significantly from 357.70 nm to 43.55 nm, as shown in Figure S7. The average grain size of the products demonstrates a gradual decrease with the increase of glycerol content, from 357.7 nm (0 wt.%) to 124.15 nm (6.7 wt.%), 94.03 nm (10 wt.%) and 43.55 nm (20 wt.%). This substantial reduction in the grain size significantly increased the specific surface area of the products.

Fig. 3 Comparison of product morphology with and without glycerol addition. a SEM, AFM, and side cross-sections without glycerol, with the addition of 10 vol.% glycerol and different scanning times of FsLDW. b Trend of product surface roughness with glycerol content; c Schematic diagram of the synthesis of products through FsLDW with and without glycerol addition.

We conducted UV-VIS-NIR absorption spectroscopy on the precursors with and without glycerol to investigate the role of glycerol in the precursors, as shown in Figure S8. The results indicated nearly no difference in the absorption spectra. Therefore, we believe that glycerol did not alter the main components of the precursor. To further explore the mechanism of action of glycerol, we performed a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis of the precursors, as shown in Figures S9–S11. Figure S9 shows the substances and their relative molecular masses, as detected by LC-MS analysis. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed using both positive and negative ion modes for the precursors with and without 20 vol.% glycerol, as shown in Figure S10. The characteristic spectral peaks of the solute molecules in the precursors are nearly identical. However, the precursor with 20 vol.% glycerol exhibited lower-intensity characteristic peaks of the hydrolysis intermediates, with mass-to-charge ratios of 155 (zinc hydroxide with an MEA chelate ring) and 199 (zinc hydroxy acetate). In addition, the peak intensities of zinc acetate with the MEA chelate ring, with mass-to-charge ratios of 241, 309, and 369, increased in the precursor-containing glycerol, indicating that adding glycerol had a significant inhibitory effect on the hydrolysis of zinc ions. For the condensation of the hydrolysis products, Figure S11 shows the characteristic peaks of the products with mass-to-charge ratios greater than 400. Adding glycerol considerably reduced the peak intensities of the products with mass-to-charge ratios greater than 800. Furthermore, the peak intensities of components with mass-to-charge ratios between 400–800 were significantly reduced in the negative ion mode, indicating that glycerol also inhibits the condensation process. Therefore, the inhibitory effects of glycerol on hydrolysis and condensation resulted in a more homogeneous precursor composition, contributing to the consistency of the products obtained by FsLDW. In addition, owing to the addition of glycerol, a large amount of hydrogen bonding significantly increases the viscosity of the precursor44,45. This high-viscosity solution effectively inhibits nanoparticle aggregation. Thus, we believe that with the addition of glycerol, the inhibition of the hydrolysis-condensation reaction during precursor preparation and the spatial hindrance effect during grain growth effectively prevented the uncontrolled growth and aggregation of the ZnO grains, resulting in smaller particle sizes and more uniform morphologies.

To better explain this mechanism, we divided the synthesis process into four stages: the nucleation stage of the precursor components, the growth stage of the nanoparticles, the aggregation stage of the ZnO nanoparticles, and the patterning stage of the nanoparticles through femtosecond laser scanning, as shown in Fig. 3c. In the absence of glycerol, high condensation levels and uncontrolled particle growth resulted in large and inhomogeneous ZnO particles, leading to high roughness and uneven morphology during the aggregation and patterning stages. However, adding glycerol inhibited hydrolysis and condensation of the solute. In addition, the increased viscosity of the precursor caused by glycerol contributes to a spatial hindrance effect, effectively preventing the uncontrolled growth and aggregation of ZnO. However, the amount of glycerol that can be added to the precursor is limited. Glycerol content exceeding 25 vol.% will suppress the formation of ZnO products during FsLDW due to the inhibition of hydrolytic condensation and grain formation.

Dark current is a decisive factor affecting the signal-to-noise ratio and power consumption of photosensitive detectors. We believe that the grain-size modulation effect of glycerol, which results in smaller grains and a larger specific surface area, is crucial for achieving photosensitive detectors with extremely low dark currents. Thus, using the glycerol-assisted FsLDW method, we successfully fabricated a series of ZnO-based UV photodetectors. Fig. 4a, b show a schematic and optical micrograph of the device, respectively. The active layer of the detector, composed of ZnO synthesized using FsLDW, contained 11 ZnO products with line widths of approximately 1 μm. Subsequently, a Cr/Au interdigital electrode was fabricated using photolithography and physical vapor deposition. The I-V curve for the device with 20 vol.% glycerol addition is shown in Fig. 4c with an on/off ratio of 2.8 × 105, responsivity of 2.78 × 102 A/W, and ultra-low dark current less than 10 pA. The dark current was lower than the detection limit of the instrument. For comparison, we measured the UV detection performance of ZnO nanomaterial products synthesized from a precursor without glycerol, with the results shown in Fig. 4d. Compared with the characterization results of devices with glycerol, those without glycerol exhibited a three-orders-of-magnitude increase in the dark current. Furthermore, we investigated the UV detection performance of the products at varying glycerol concentrations, as shown in Figure S12. The switching ratio of the device increased gradually with increasing glycerol content, consistent with the trend of the product particle size. However, with the addition of excess glycerol (25 vol.%), its inhibitory effect on hydrolysis and condensation leads to difficulties in product formation, which results in the reappearance of discontinuities and deterioration of UV response properties. Table S1 summarizes the performances of the reported ZnO-based UV photodetectors. In comparison, the dark current of our device is lower by more than one order of magnitude at the same bias voltage, with a considerable on/off ratio and responsivity. Fig. 4e, f show the time-resolved responses of the device at a bias of 10 V. The measured device rising and falling times were approximately 90 s and 48 s, respectively. Notably, the time-resolved response of ZnO (Fig. 4f) shows a gradual increase in its maximum photocurrent upon repeated UV pulses, possibly attributed to the persistent photoconductivity of the metal oxides, which allows the imitation of synaptic plasticity through optical stimulation. This phenomenon is expected to be useful in optical neuromorphic devices, such as optoelectronic neurons or synapses. Further investigations in this area will be conducted in our future work46.

Fig. 4 ZnO-based UV photodetector fabricated by FsLDW. a Schematic diagram and b optical micrograph of the ZnO-based photodetector; the inset is the partially enlarged image. c, d I-V curve (logarithmic coordinates) of ZnO-based UV photodetector under 365 nm UV light with 20 wt.% glycerol and without glycerol. e Rising and falling time of the detector. f Time-resolved response of ZnO-based UV photodetector under 365 nm UV light at 10 V bias.

Previous studies have shown that the ultraviolet photoelectric detection of ZnO is directly related to the oxygen molecules adsorbed on its surface47. The ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using FsLDW without glycerol exhibited large and heterogeneous particle sizes, causing them to agglomerate severely and reduce their specific surface area. This process resulted in relatively fewer adsorbed oxygen molecules, leading to a thinner depletion layer and higher dark current. The inhibitory effect of glycerol on the hydrolysis and condensation processes in the precursor, along with its spatial hindrance during FsLDW, resulted in reduced grain size and significantly increased specific surface area, which increased the capacity for oxygen molecule absorption. The surface-adsorbed oxygen molecules form depletion layers within the ZnO grains, thereby reducing the concentration of charge carriers in the dark, which increases the resistivity of ZnO in the dark and lowers the dark current. Smaller grain size and larger specific surface area resulted in a greater proportion of the depletion layer within the ZnO grains, resulting in an ultralow dark current. Similar glycerol-assisted FsLDW techniques can be employed to fabricate other metal oxide nanomaterials, such as tin, nickel, and titanium oxides, which is of great significance for improving the performance of functional devices based on surface effects, such as in gas sensing and catalysis.

-

We propose an FsLDW technique for in-situ synthesis of designable ZnO nanomaterial micropatterns without masks or laser-absorbing layers through a multiphoton photochemical reaction. Moreover, by incorporating glycerol additives, we reduced the grain size, increased the specific surface area, and effectively enhanced the consistency and uniformity of the products, thereby overcoming bottlenecks encountered during the fabrication of integrated functional devices. This enhancement by glycerol is primarily attributed to its inhibitory effect on precursor hydrolysis and condensation processes, along with its spatial hindrance during the FsLDW process. Using this technique, we prepared ZnO-based UV photodetectors with a switching ratio of up to 105, a responsivity of up to 102 A/W, and an ultralow dark current of less than 10 pA. The dark current is more than one order of magnitude lower than that of previously reported ZnO UV photodetectors. We believe the increased specific surface area resulting from glycerol addition is the primary factor contributing to the ultralow dark current. This FsLDW method simplifies the synthesis and device preparation process for ZnO nanomaterials with a high specific surface area and can be applied to synthesize multi-metal oxides, N- and P-type metal oxides, and other metal oxides by adding different elements to the precursors. This technique offers considerable potential for developing micro/nanofunctional devices and efficiently promotes the integration, miniaturization, and customization of functional microdevices based on metal oxide nanomaterials.

-

First, 0.54 g of zinc acetate dihydrate powder was dissolved in 5 mL of 2-methoxyethanol (EGME), followed by the addition of 0.155 mL of 2-aminoethanol (MEA). The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, glycerol was added to the as-prepared sol at concentrations varying from 0 to 25 vol.% and stirred for 12 h at room temperature to obtain a uniformly mixed solution.

-

A 20 × 20 × 0.17 mm soda-lime glass was employed as the substrate for this work. The substrate was cleaned ultrasonically for 15 min using acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water. After drying, oxygen plasma was applied for 5 min to make the surface hydrophilic—beneficial for spin-coating the precursor (the processing equipment was evacuated to below 100 Pa, the O2 gas flow was set to 100 cc/min, and the RF power was set to 90 W). The precursor was spin-coated onto the substrate (500 rpm, 5s; 3000 rpm, 25 s) and mounted on the sample holder of a femtosecond laser processing system.

A Ti:sapphire femtosecond laser (Coherent Company Chameleon Discovery Series) with a repetition rate of 80 MHz, a pulse width of 100 fs, and a laser wavelength of 780 nm was used. An oil-immersion objective lens (60×, NA 1.4, Olympus) focused the laser beam onto the precursor. The scanning speed varies from 10 to 100 μm/s, and the laser power varies from 60 to 120 mW. The scanning path of the laser focal point was controlled using a galvanometer or two-axis stage system. After FLDW, the samples were immersed in EGME for 30 min and washed with ethanol and deionized water.

-

ZnO products first undergo a high-temperature annealing process (350 ℃, 2 h, O2 atmosphere) to remove organic impurities. The lift-off method was used in this study to prepare the metal electrodes. The photoresist used, i.e., AZ5214, was exposed to a 405 nm light source. Electron beam evaporation was used to deposit the Cr/Au electrode, and N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) was used to exfoliate the photoresist. The photodetector response was measured using a B1500A semiconductor parameter analyzer (Yestech, Singapore) with a 365-nm halogen lamp and a light intensity of 2 mW/cm2.

-

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers 52275429 and 62205117). The authors thank the Analytical and Testing Center of HUST, the facility support of the Center for Nanoscale Characterization and Devices at the Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics, and technical support from the Experiment Center for Advanced Manufacturing and Technology at the School of Mechanical Science and Engineering of HUST.

Glycerol-assisted grain modulation in femtosecond-laser-induced photochemical synthesis of patterned ZnO nanomaterials

- Light: Advanced Manufacturing , Article number: (2025)

- Received: 03 July 2024

- Revised: 19 November 2024

- Accepted: 02 December 2024 Published online: 07 March 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.37188/lam.2025.007

Abstract: ZnO nanomaterials have become appealing for next-generation micro/nanodevices owing to their remarkable functionality and outstanding performance. However, in-situ, one-step, patterned synthesis of ZnO nanomaterials with small grain sizes and high specific surface areas remains challenging. While breakthroughs in laser-based synthesis techniques have enabled simultaneous growth and patterning of these materials, device integration restrictions owing to pre-prepared laser-absorbing layers remain a severe issue. Herein, we report a single-step femtosecond laser direct writing (FsLDW) method for fabricating ZnO nanomaterial micropatterns with a minimum linewidth of less than 1 μm without requiring laser-absorbing layers. Furthermore, utilizing the grain-size modulation effect of glycerol, we successfully reduced the grain size and addressed the challenges of discontinuity and non-uniform product formation during FsLDW. Using this technique, we successfully fabricated a series of micro-photodetectors with exceptional performance, a switching ratio of 105, and a responsivity of 102 A/W. Notably, the devices exhibited an ultralow dark current of less than 10 pA, more than one order of magnitude lower than the dark current of ZnO photodetectors under the same bias voltage—crucial for enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio and reducing the power consumption of photodetectors. The proposed method could be extended to preparing other metal-oxide nanomaterials and devices, thus providing new opportunities for developing customized, miniaturized, and integrated functional devices.

Research Summary

Grain Modulation during femtosecond laser direct writing for larger specific surface area

ZnO nanomaterials have become appealing for next-generation micro/nanodevices. However, in-situ, one-step, patterned synthesis of ZnO nanomaterials with high specific surface areas remains challenging. Wei Xiong from Huazhong University of Science and Technology and colleagues report a glycerol-assisted femtosecond laser direct writing (FsLDW) method for fabricating ZnO nanomaterial micropatterns. Utilizing the inhibitory effect of hydrolysis and condensation processes and spatial hindrance effect of glycerol, they successfully reduced the grain size and addressed the challenges of discontinuity product formation during FsLDW. The larger specific surface area significantly reduced the dark current of the ZnO photodetector. The proposed method could be extended to preparing other metal-oxide nanomaterials and devices, thus providing new opportunities for developing customized, miniaturized, and integrated functional devices.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article′s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article′s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: