-

Lead halide perovskite quantum dots (QDs) have received significant research attention owing to their exceptional luminescence properties, such as size-tunable emission, heightened optical gain performance, high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), and potential for facile and cost-effective solution-processing methods1–5. The unique performance of perovskites aids in the rapid development of the application prospects of advanced optoelectronic devices6–10. In particular, perovskite QDs are potential candidates for new gain media used for amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) and lasers, thus offering considerable potential for miniaturized laser devices11–17. For instance, Yakunin et al. demonstrated ASE from CsPbX3 QDs with a low pumping energy density threshold (down to 5 μJ·cm−2)18. Further, Yang et al. reported ASE with a low threshold from perovskite QDs in a superlattice microcavity (down to 9.45 μJ·cm−2)19.

Notably, preparing high-quality QDs is a prerequisite to ensure excellent ASE properties. Among the various synthesis methods for perovskite QDs, the hot-injection method has attracted widespread attention owing to its simplicity, ease of use, and cost-effective synthesis process20. However, despite its many advantages, some problems have been encountered during the hot-injection process. Generally, oleylamine (OAm) and oleic acid (OA) are used as capping agents in QDs synthesis. QDs synthesized with long-chain organic OAm and OA are sensitive to proton exchange between the surface ligands and QDs. This process leads to ligand desorption and QDs instability because OAm and OA easily detach from the QDs surface during storage and post-processing, which leads to a high density of trap states and reduces the spontaneous radiation rate of QDs20,21. Moreover, owing to the chemical equilibrium between the cesium resources dissolved in OA and the cesium oleate (CsOL) precursor in traditional recipes, where cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) is used to prepare the CsOL precursor, the solubility and reactivity state of the CsOL precursor also affect the nucleation and growth process of QDs. However, the inherent low solubility of the CsOL precursor derived from Cs2CO3 results in the incomplete and insufficient conversion of Cs2CO3, leading to an increase in precipitate content when cooled to room temperature. This result is consistent with the images of the Cs2CO3 precursor obtained at different temperatures in this study (Supplement Fig. S1)22,23. This low conversion rate leads to a substantial amount of unconverted Cs2CO3 along with by-products such as cesium-containing mixtures, consequently preventing a portion of cesium from participating in the synthesis of QDs. Constrained by this uncertainty, the final products show vast differences in size, morphology, and optical properties in each batch, indicating reduced reproducibility of the QDs. Hence, further enhancing the homogeneity and reproducibility of QDs is essential to achieve industrialized goals for perovskites.

With the emergence of perovskite lasers, the prevailing development trend for semiconductor lasers is toward microlasers with low thresholds. However, in previous studies, some challenges were encountered when preparing perovskite QDs as a gain medium, including surface defects, deep-level traps caused by crystal lattice irregularities, and multiexciton Auger non-radiative recombination24,25. Among these challenges, Auger non-radiative recombination is a key factor limiting the performance of low-threshold lasers. Auger non-radiative recombination rapidly depletes multiple excitons and becomes a prominent factor at high carrier densities, leading to a brief duration of sustained optical gain, mainly attributed to the competitive relationship between biexciton-stimulated emission and Auger non-radiative recombination. In general, a more extended biexciton-stimulated emission lifetime results in a lower laser threshold. Therefore, reducing Auger non-radiative recombination is an effective strategy for achieving an ASE with a lower threshold26. Trap states are key factors in these challenges. The incomplete trap-filling surface of the QDs under excitation accelerates trap-assisted non-radiative recombination, further deteriorating the ASE properties of the QDs. To reduce the influence of these factors, Jiang et al. demonstrated a ligand replacement method to suppress Auger and trap-assisted recombination processes by utilizing a molecular passivation agent without compromising PLQY6.

Herein, we present a facile and practical synthesis strategy based on cesium precursor optimization using the dual-functional acetate ligand (AcO−) and short-branched-chain ligand 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA). First, the origin of the poor reproducibility of QDs synthesized from the common cesium precursor Cs2CO3 was identified, which demonstrated that the low solubility of Cs2CO3 led to the presence of a substantial amount of by-products in the reacted CsOL precursor at low temperatures, seriously affecting the homogeneity, reproducibility, and optical properties of the QDs products. This limitation was overcome by replacing Cs2CO3 with cesium acetate (CsOAc), which resulted in the complete conversion of CsOL even at room temperature. Therefore, pure CsOL can expedite the nucleation and growth kinetics of the QDs and enhance their reproducibility and batch-to-batch consistency. Moreover, AcO− can act as a surface ligand to passivate dangling bonds on the QDs surface, thereby enhancing the optical performance and stability of the QDs. In addition, 2-HA served as a surface ligand, further improving the optical properties. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations show that 2-HA exhibits stronger absorption energy with QDs than with OA, which can efficiently stabilize the surface of QDs and inhibit ligand desorption, thus improving the stability of QDs. The results of the photoexcited carrier dynamics indicate that 2-HA can passivate surface defects and decrease the exciton binding energy ($ {E}_{\mathrm{B}} $), which can suppress non-radiative trap-assisted and Auger recombination, thus overcoming the weak spontaneous emission rate of perovskites. The optimized QDs exhibited a high PLQY of 99%, excellent stability, and a narrow full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 22 nm. Furthermore, the ASE threshold of optimized QDs reduced by 70% from 1.80 μJ·cm−2 to 0.54 μJ·cm−2. These findings highlight the importance of cesium precursors in improving the reproducibility and suppressing the non-radiative recombination process, particularly for realizing high-efficiency laser devices.

-

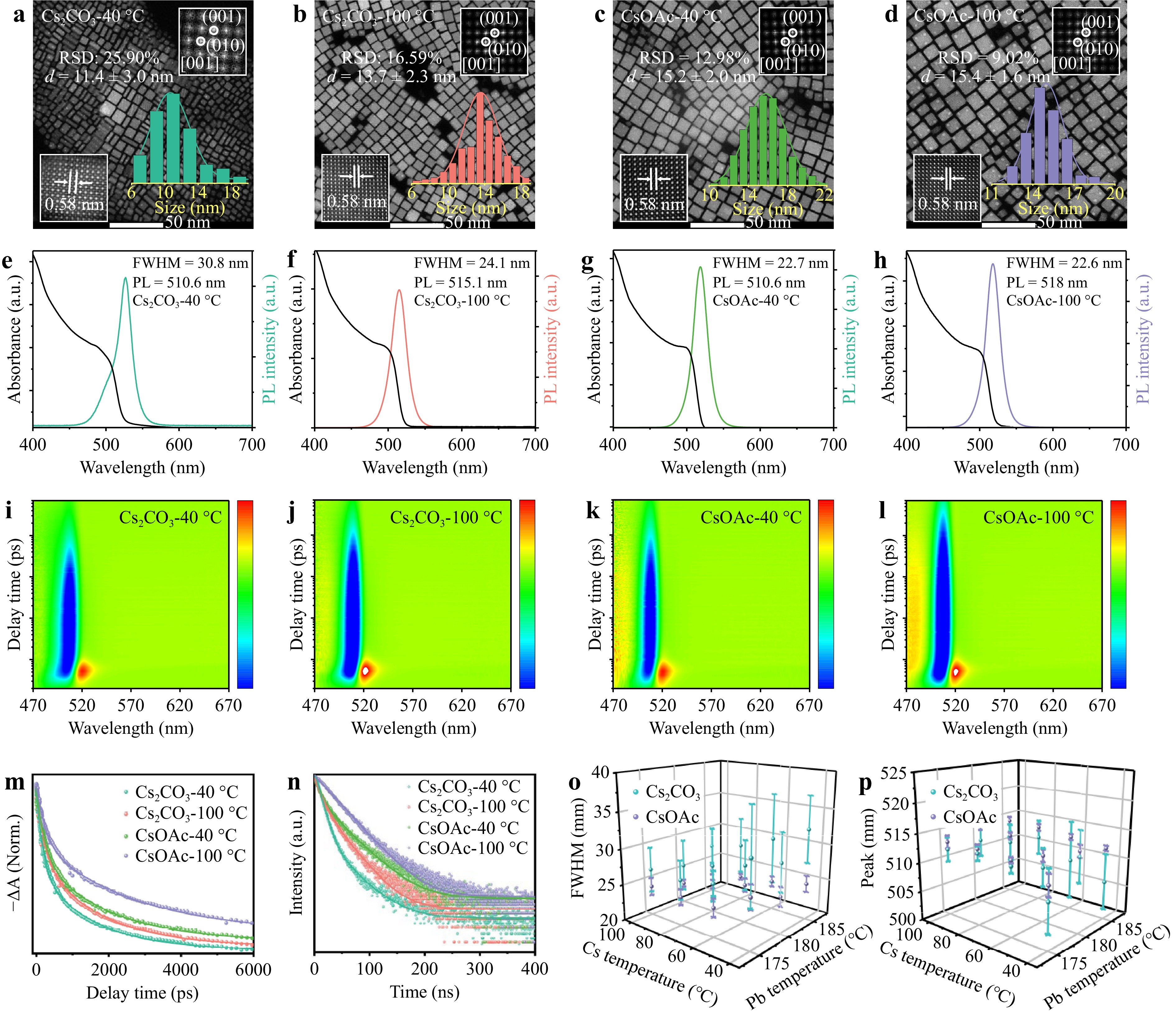

In this study, CsPbBr3 QDs were prepared using two types of Cs sources (Cs2CO3 and CsOAc). For comparative analysis of the solubility of CsOL during the conversion process, different CsOL precursors were prepared using these cesium salts at different temperatures. Based on these CsOL precursors, representative QDs were prepared by utilizing Cs2CO3 as a cesium resource at 40 °C (Cs2CO3-40 °C), and at 100 °C (Cs2CO3-100 °C), as well as synthesized using CsOAc as cesium resource at 40 °C (CsOAc-40 °C), and at 100 °C (CsOAc-100 °C). Fig. 1a-d and Supplement Fig. S2 show transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) results for the QDs. Cs2CO3-40 °C QDs exhibited uneven size distribution (11.4 ± 3.0 nm) and irregular morphology, accompanied by nanosheets and differently shaped by-products, thus highlighting the difficulties in obtaining excellent QDs via several different batches with the same synthesis process. Cs2CO3-100 °C QDs exhibited a homogeneous cubic shape with uniform size distribution (13.7 ± 2.3 nm). More importantly, the cesium concentration of the CsOL precursor used for these QDs was measured by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analysis, with the conversion of CsOL found to range from 70.26% to 98.59%, as presented in Supplement Table S1, related to the solubility of Cs2CO3 in octadecene (ODE) and OA, which decreases with decreasing CsOL temperature. A considerable amount of precipitate was formed when the temperature was below 40 °C (Supplement Fig. S1). Instead, both CsOAc-100 °C and CsOAc-40 °C QDs exhibited a homogeneous size distribution and regular morphology (15.2 ± 2.0 and 15.4 ± 1.6 nm). Furthermore, under low-temperature conditions, the CsOAc precursor does not form precipitates, further verifying our viewpoint27. Fig. 1e-h demonstrate that the photoluminescence (PL) emission spectrum of Cs2CO3-40 °C QDs exhibits apparent asymmetry on both sides with wider FWHM of 30.8 nm than that of Cs2CO3-100 °C QDs (24.1 nm), consistent with the poor size distribution of Cs2CO3-40 °C QDs. However, QDs synthesized using CsOAc show a symmetrical PL peak with narrow FWHM of 22.6 and 22.7 nm, which strongly demonstrates that the solubility of CsOAc in ODE is less susceptible to the holding temperature.

Fig. 1 Morphology and optical properties of the perovskite CsPbBr3 QDs: TEM images, UV–vis absorption spectra, and PL spectra, and pseudo color image of TA of a, e, i Cs2CO3-40 °C, b, f, j Cs2CO3-100 °C, c, g, k CsOAc-40 °C, and d, h, l CsOAc-100 °C QDs, respectively. Insets show the corresponding size distribution histograms, FFT, and IFFT images. m TA bleach dynamics curves and n time-resolved PL-decay spectra of Cs2CO3-40 °C, Cs2CO3-100 °C, CsOAc-40 °C, and CsOAc-100 °C QDs. Error bar plot for the o FWHM and p peak wavelength of different QDs based on over 50 batches.

Time-resolved PL (TRPL) and femtosecond transient absorption (TA) spectra were obtained to further explore the effects of different cesium precursors on carrier recombination. Fig. 1i-l show that all these QDs exhibit ground-state bleaching (GSB) signals at approximately 510 nm while excited electrons are fitted at the 1s level of the conduction band and carrier recombination occurs, indicating band-edge bleaching phenomena and subsequent recovery via a combination of radiative and non-radiative processes28. Herein, the GSB recovery was utilized to analyze the carrier recovery dynamics, and a biexponential function was applied to fit it, as shown in Fig. 1m and Supplement Table S2. The recovery kinetics study involves two lifetime constant components; namely, the fast component (τ1), attributed to the trap-assisted Auger recombination, and the slow component (τ2), which arises from intrinsic edge exciton recombination29. Cs2CO3-40 °C QDs (τ2, 1388.3 ps, 89.2%) exhibit the faster slow component and higher ratio compared with Cs2CO3-100 °C QDs, indicating higher defects density of Cs2CO3-40 °C QDs. However, when Cs2CO3 was replaced with CsOAc, the QDs exhibited similar and low ratio of the fast components to slow components, irrespective of the temperature of 100 or 40 °C, reflective of a serious non-radiative relaxation process in the CsPbBr3 QDs prepared using Cs2CO3 at room temperature and further confirming that using AcO− as a cesium resource can effectively remove defect states and enhance the stability of the QDs30,31. Fig. 1n and Supplement Table S3 present that the PL lifetime of CsOAc-40 °C and CsOAc-100 °C QDs are 29.1 and 34.0 ns, separately. Both are longer than those of Cs2CO3-40 °C (19.8 ns) and Cs2CO3-100 °C QDs (22.2 ns). In particular, the curve corresponding to CsOAc-100 °C QDs could be fitted with a single exponential function, but other curves were described by a bi-exponential function. Irrespective of the holding temperature of CsOAc as the cesium resource, QDs with a low surface defect density could still be obtained in this study. In contrast, for QDs synthesized using Cs2CO3 as a precursor, when the holding temperature of CsOL was below 100 °C, the optical properties of QDs declined dramatically. Thus, we speculate that the raw materials of the cesium precursor affect the final quality of the QDs. in Fig. 1o, p, we summarize the relationship between the optical performance of QDs, holding temperature, and type of cesium precursor. By employing a systematic method, we vary the holding temperatures of the cesium resource and make a change of fluctuations for ± 5 °C around the injection temperature of the lead resource to study the FWHM and the peak wavelength of the QDs. The error bar plots for the FWHM and peak wavelength show that the error bar variance of both the FWHM and peak wavelength utilizing CsOAc was far less than those of Cs2CO3. Notably, increasing the holding temperature of the cesium precursor is useful for improving the overall morphological characteristics of numerous synthetic processes utilizing Cs2CO3. More importantly, combined with the homogeneous size distribution and regular morphology of the QDs obtained using CsOAc as a cesium source, irrespective of the holding temperature of the cesium resource or the injection temperature of the lead precursor, the QDs synthesized from CsOAc always exhibited good batch-to-batch consistency and reproducibility. CsOAc-100 °C QDs show a high PLQY (95%), significantly higher than that of Cs2CO3-100 °C QDs (87%). Moreover, Supplement Fig. S3 confirms the high PLQY of the QDs obtained from CsOAc as the Cs resource in every synthesis process. Therefore, AcO− can efficiently reduce the surface defects of QDs and inhibit non-radiative recombination, thereby improving the PLQY31. Furthermore, the dispersion plot for the PLQY, FWHM, peak wavelength, and size distribution of these QDs showed that AcO− could improve the reproducibility of the QDs, as shown in Supplement Fig. S4.

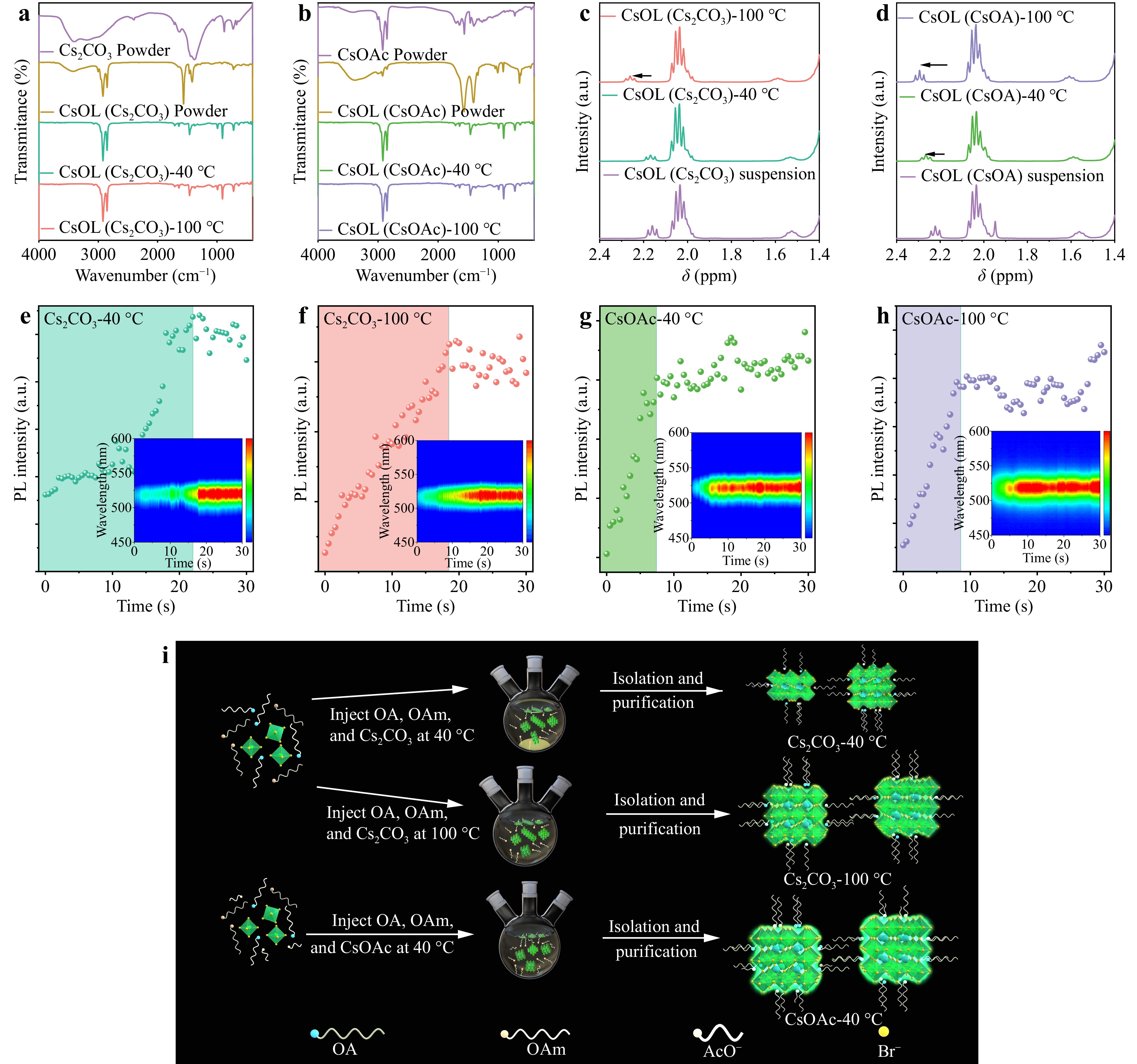

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy were performed to systematically explore the effects of cesium precursors prepared from CsOAc or Cs2CO3 on the nucleation and growth of QDs. Fig. 2a, b present the FTIR spectra of the supernatant and precipitate samples of CsOAc and Cs2CO3 at different temperatures, and their peak characteristics are summarized in Supplement Table S4. The spectrum of the CsOL (Cs2CO3) supernatant was similar to that of the CsOL (CsOAc) supernatant at all wavenumbers. The peaks at 1711 and 1540 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibrations of C=O present in Cs2CO3 or CsOAc. 1H NMR spectroscopy results are illustrated in Fig. 2c, d and Supplement Fig. S5. In principle, the 1H NMR peak of the hydroxyl group adjacent to the carbon in CsOL reflects its Cs:OA ratio, which can be attributed to the conversion of CsOAc or Cs2CO3 to CsOL. A larger value of the carbon peak corresponds to a higher CsOL conversion rate. With increasing holding temperature of Cs2CO3 as the cesium source, the 1H NMR peak of the hydroxyl group adjacent to the carbon in OA shifts from 2.15 to 2.40 ppm. This chemical shift is attributed to an increase in the Cs:OA concentration ratio in the precursor solution. Therefore, a comparative analysis of the 1H NMR spectra of CsOL prepared using CsOAc and Cs2CO3 indicates that the difference in these chemical shifts suggests that the solubility of CsOAc in OA is much higher than that in Cs2CO3, even at room temperature, consistent with the characteristic resonances and the FTIR spectroscopy result22. Therefore, we speculate that AcO− could accelerate the transformation of cesium salts to CsOL. In-situ PL spectroscopy of these QDs was conducted to explore the effect and mechanism of AcO− during the nucleation and growth processes, as depicted in Fig. 2e-h. The in-situ PL emission spectra exhibited a continual increase in intensity, eventually reaching a stable state after a short duration (termed the setup time) during the synthesis process. Interestingly, with an increase in the holding temperature of the cesium precursor prepared from Cs2CO3, the setup time decreased from 19.5 to 17 s. In contrast, when CsOAc was used as the cesium precursor, the setup time was approximately 8 s, independent of the holding temperature of CsOL. This substantial disparity in setup time indicates the effect of AcO− on expediting the nucleation and growth kinetics of the QDs32. Moreover, this result was also proven by the evolution of the FWHM during the nucleation and growth processes (Supplement Fig. S6). To further analyze the mechanism of AcO− in the synthesis of QDs, TEM, PL spectroscopy, ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy, and transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy of the QDs obtained using OA and HOAc or HOAc as cesium resources, as shown in Supplement Figs. S7–S9. Fig. 2i shows the synthesis of QDs employing Cs2CO3 and CsOAc under varying holding temperatures. When Cs2CO3 was used at a low temperature, a large amount of precipitate was formed, which led to non-uniform QDs sizes and the notable presence of defects and by-products in the QDs. However, these challenges, owing to the influences of solubility, size distribution, and surface dangling bonds, were overcome by replacing Cs2CO3 with CsOAc, and even the holding temperature of the cesium precursor could be decreased to room temperature. Therefore, AcO− served as a surface ligand and improved the stability, surface defects, and batch-to-batch uniformity of the QDs, thus accelerating the nucleation and growth process and shaping the low defect density of the QDs.

Fig. 2 Influence mechanism of AcO− on the QD growth process: FTIR spectra of powder and CsOL supernatant at 40 °C and 100 °C prepared from a Cs2CO3 and b CsOAc. 1H NMR spectra of isocratic and saturated CsOL supernatant at 40 °C and 100 °C prepared from c Cs2CO3 and d CsOAc. In-situ PL spectra of e Cs2CO3-40 °C, f Cs2CO3-100 °C, g CsOAc-40 °C, and h CsOAc-100 °C QDs. i Schematic illustration of the influence mechanism of AcO− on the QDs growth process.

-

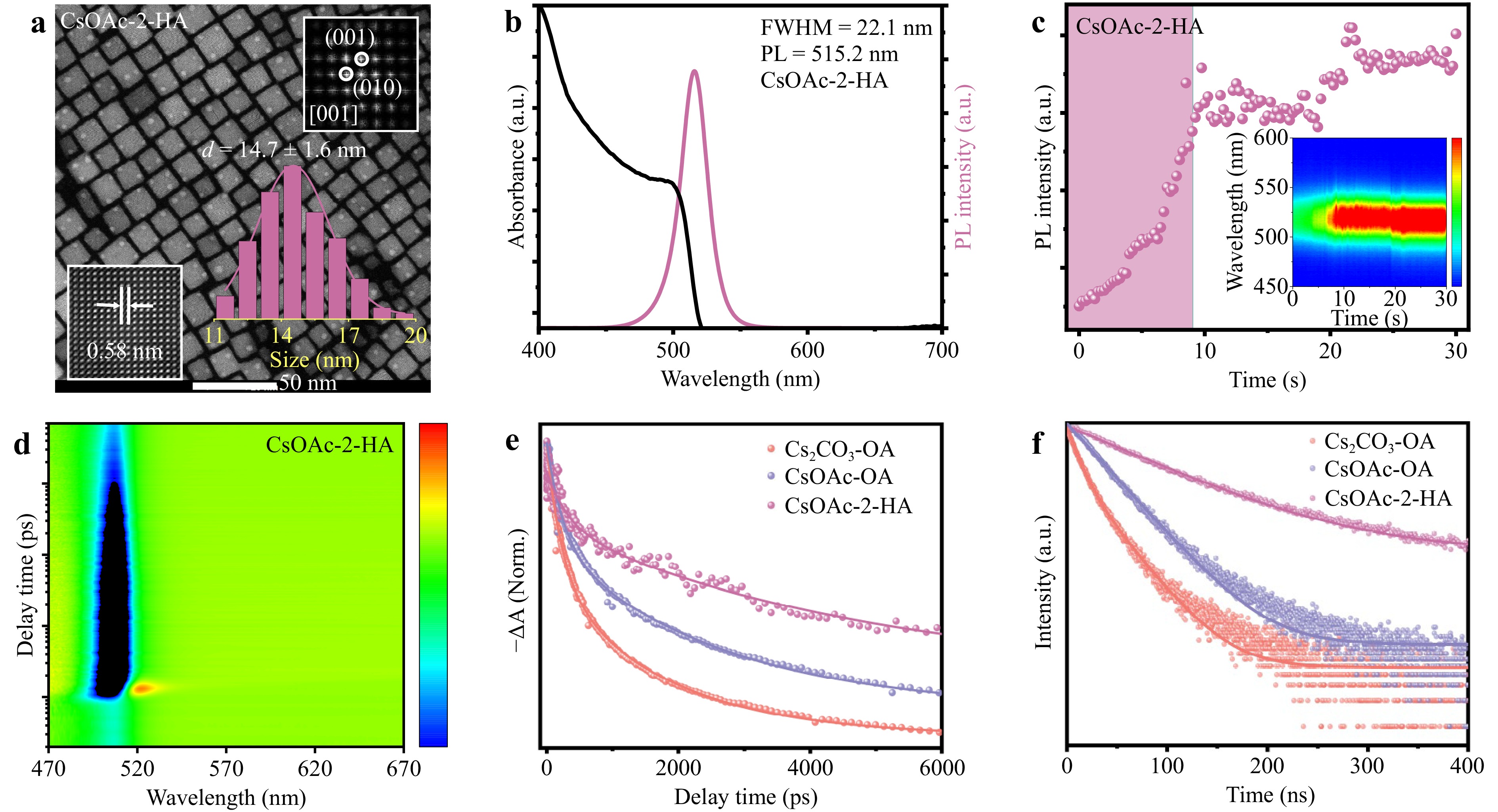

In the conventional synthesis of perovskite QDs, OA and OAm are employed as surface ligands; however, these long-chain organic ligands exhibit a relatively weak binding affinity with QDs, which diminishes the spontaneous emission rates of QDs33. Therefore, a precursor prepared from CsOAc and the short branched-chain ligand 2-HA was designed as a substitute for OA. Importantly, the solubility of the CsOL precursor prepared by mixing CsOAc with 2-HA and ODE is independent of the holding temperature, as shown in Supplement Fig. S1. Fig. 3a, b exhibit the TEM images, PL spectra, and UV spectra of the QDs synthesized from AcO− and 2-HA (named CsOAc-2-HA QDs). The TEM images of CsOAc-2-HA QDs indicate smaller sizes with uniform size distribution of 14.7 ± 1.6 nm and narrow FWHM of 22.1 nm, slightly better than that of QDs obtained using AcO− and OA at 100 °C (named as CsOAc-OA) and better than that of QDs prepared using Cs2CO3 and OA at 100 °C (named as Cs2CO3-OA), attributed to the fact that short-chain 2-HA and AcO− can get closer to each other with the QDs surface and acquire sufficient space for molecules on adjacent particles to penetrate each other34,35. Hence, the short branched-chain ligand 2-HA can prevent the contact of small species from attaching to the QDs surface compared to OA, which can further suppress the ultrafast growth dynamics of QDs and inhibit Ostwald ripening during the nucleation and growth process of QDs. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis showed the same results, as elucidated and discussed in Supplement Fig. S10. Considering the growth and nucleation processes of the in-situ PL spectrum of CsOAc-2-HA QDs were obtained, as shown in Fig. 3c. Compared with the setup time of CsOAc-OA QDs, the in-situ PL intensity spectrum of CsOAc-2-HA QDs exhibited a similar setup time (8.5 s) to reach stability, which indicates that the nucleation and growth processes are free from the influence of 2-HA without compromising the PLQY (99%), as presented in Supplement Table S3.

Fig. 3 Optical properties of the perovskite CsPbBr3 QDs prepared with 2-HA: a TEM images, b UV–vis absorption and PL spectra, c in-situ PL spectra, d pseudo-color TA plot of CsOAc-2-HA QDs. Insets show the corresponding size distribution histograms, FFT, and IFFT images. e TA bleach recovery curves, and f time-resolved PL-decay transients of Cs2CO3-OA, CsOAc-OA, and CsOAc-2-HA QDs.

The TA spectrum of the CsOAc-2-HA QDs is shown in Fig. 3d, and the transient dynamic curves of the QDs are presented in Fig. 3e, with fitting parameters elucidated in Supplement Table S2. Clearly, the rate of descent of the transient dynamics curves of the CsOAc-2-HA QDs was longer than that of the other QDs. CsOAc-2-HA QDs exhibited a long excited-state lifetime of 4638 ps, surpassing that of the other QDs and even reaching close to twice that of CsOAc-OA QDs. Moreover, the longer lifetime and stronger bleaching of the CsOAc-2-HA QDs indicated that 2-HA enhanced the suppression of the density of non-radiative trap centers. The TRPL results are illustrated in Fig. 3f, while the fitting parameters are presented in Supplement Table S3. The PL decay dynamics of the CsOAc-2-HA QDs can be fitted by a single-exponential function, featuring an exciton lifetime far exceeding that of Cs2CO3-OA. Compared to CsOAc-OA and Cs2CO3-OA QDs, the high PLQY of 99% and low non-radiative recombination rate of 0.012 ns−1 clearly demonstrated that CsOAc-2-HA QDs dramatically reduce non-radiative recombination36. Based on the combined analysis of the PL decay and TA spectra, a common result indicates that 2-HA can further passivate non-radiative surface defects and reduce non-radiative surface defect centers compared with CsOAc-OA because of the higher binding energy between the QDs and 2-HA than that of OA (Supplement Fig. S11). Therefore, 2-HA also effectively suppresses non-radiative recombination, enhances optical performance, and improves the PLQY of CsOAc-2-HA QDs37. To study the thermal stability of the QDs, they were continuously heated to different temperatures to simulate the environment of laser excitation, and the corresponding PL spectra were collected, as shown in Supplement Fig. S12. CsOAc-2-HA QDs showed less decay of the PL intensity at the same heating temperature, indicating the better thermal stability of CsOAc-2-HA QDs. Furthermore, Supplement Fig. S13 shows the dependence of QDs PL intensity on time. In general, CsOAc-2-HA QDs can maintain spectral stability in different environments, attributed to the substantial steric hindrance and repulsion of 2-HA, and can form a denser, more congested surface ligand layer to provide better protection from the ambient environment, which can prevent small species such as H2O or O2 from attaching to the surface and degrading the QDs.

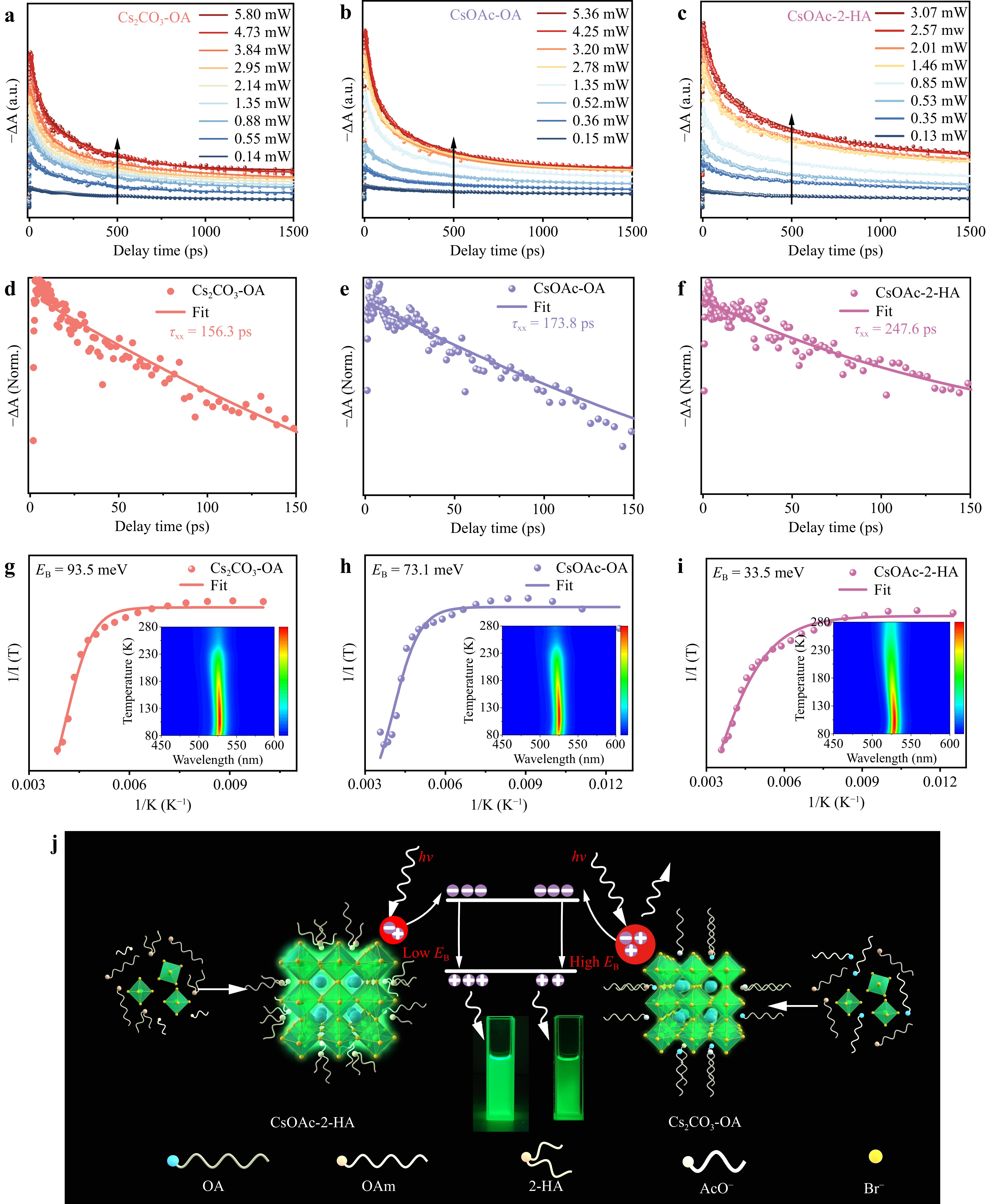

In this study, the mechanism and kinetic processes of the interactions between 2-HA and QDs were explored using temperature-dependent PL spectra. Owing to the dependent relationship between the Auger recombination process and the power of the exciton bleach, the kinetic results probed at the exciton bleach at varying pump intensities were measured, and the long-lived tail was eliminated to extract the biexciton Auger recombination. Power-dependent TA spectra were obtained to extract the biexciton Auger recombination. Given the prevalence of biexciton recombination, recognized as the primary Auger process in QDs, the widely accepted law of biexciton lifetime with QDs volume was adopted. Moreover, the investigation focused on the biexciton recombination dynamics in these QDs, as depicted in Fig. 4a-c and Supplement Fig. S14. The normalization curve related to the long-lived tail of the biexciton recombination was fitted with a single exponential function, as presented in Fig. 4d-f. The biexciton recombination lifetime of the CsOAc-2-HA QDs extends to 247.6 ps, much longer than those of the CsOAc-OA (173.8 ps) and Cs2CO3-OA QDs (156.3 ps). The long lifetime of the CsOAc-2-HA QDs suggests the effective suppression of the Auger recombination process, which contributes to reducing the ASE threshold. Furthermore, compared with the tremendous inhibition effect on Auger recombination by 2-HA, the influence of AcO− on Auger recombination is weak. On the one hand, the enhancement effect of CsOAc-2-HA QDs on stability and surface passivation suppresses the trap-assisted Auger recombination process26. On the other hand, 2-HA can reduce the $ {E}_{\mathrm{B}} $ of QDs, closely related to Auger recombination. Owing to the enhanced Coulomb electron–hole interaction, the Auger recombination rate is proportional to the third power of $ {E}_{\mathrm{B}} $26,38,39. Fig. 4g-i show the temperature-dependent photoluminescence (PL) spectra of these QDs. The exciton binding energies ($ {E}_{\mathrm{B}}) $ of the Cs2CO3-OA, CsOAc-OA, and CsOAc-2-HA QDs calculated from the temperature-dependent PL spectra were 93.5, 73.1, and 33.5 meV, respectively. Theoretically, the confinement effect is enhanced by a decrease in the size. Therefore, smaller QDs led to stronger quantum confinement effects, resulting in a higher $ {E}_{\mathrm{B}} $. This result is consistent with the larger size of the CsOAc-2-HA QDs, which can contribute to reducing $ {E}_{\mathrm{B}} $. In addition, 2-HA adjusted the distribution of the electron clouds of QDs, which alleviated the accumulation of carriers (Supplement Fig. S15), further decreasing $ {E}_{\mathrm{B}} $ and suppressing the Auger recombination process.

Fig. 4 Carrier dynamics of perovskite CsPbBr3 QDs: Power-dependent kinetic traces at the exciton bleach and isolated decay curve of biexciton Auger recombination for a, d Cs2CO3-OA, b, e CsOAc-OA, and c, f CsOAc-2-HA QDs, respectively. Temperature-dependent PL spectra of g Cs2CO3-OA, h CsOAc-OA, and i CsOAc-2-HA QDs between 80 and 280 K. Insets show the corresponding temperature-dependent PL spectra. j Schematic illustration of the passivation process employing OA and 2-HA, which results in the formation of CsOAc-OA and CsOAc-2-HA QDs.

Furthermore, the mechanism underlying the suppression of Auger recombination is explored. Supplement Fig. S16 shows the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) profiles, which show higher binding energy for the Pb-4f levels and Cs-3d levels of CsOAc-2-HA and CsOAc-OA QDs, indicating that the 2-HA and AcO− ligands undergo more powerful interactions and binding affinities with QDs than with OA40,41. To further investigate the mechanism of AcO− and 2-HA ligand modification of QDs, DFT was used to clarify the appearance of mid-gap states in Cs2CO3-OA QDs, absorption energy, and the absence of energy overlap among these QDs, as elucidated and discussed in Supplement Figs. S11 and S1542–44. In addition, due to the largest region of charge transfer from CsOAc-2-HA QDs, AcO− and 2-HA can efficiently store abundant electrons, which can reduce the influence of the dielectric mismatch effects and thus lead to the decrease in $ {E}_{\mathrm{B}} $. A comparative analysis of the QDs synthesized by treatment with 2-HA or OA is presented in Fig. 4j. The tight structure of 2-HA facilitated superior adhesion to the surfaces of the QDs, resulting in high performance of QDs characterized by heightened stability and reduced surface defects, in contrast to the Bouffant structure of OA with more surface defects and Br− ion defects. The 2-HA ligand weakened the occurrence of Auger recombination in the QDs, thereby improving the rate of spontaneous emission.

-

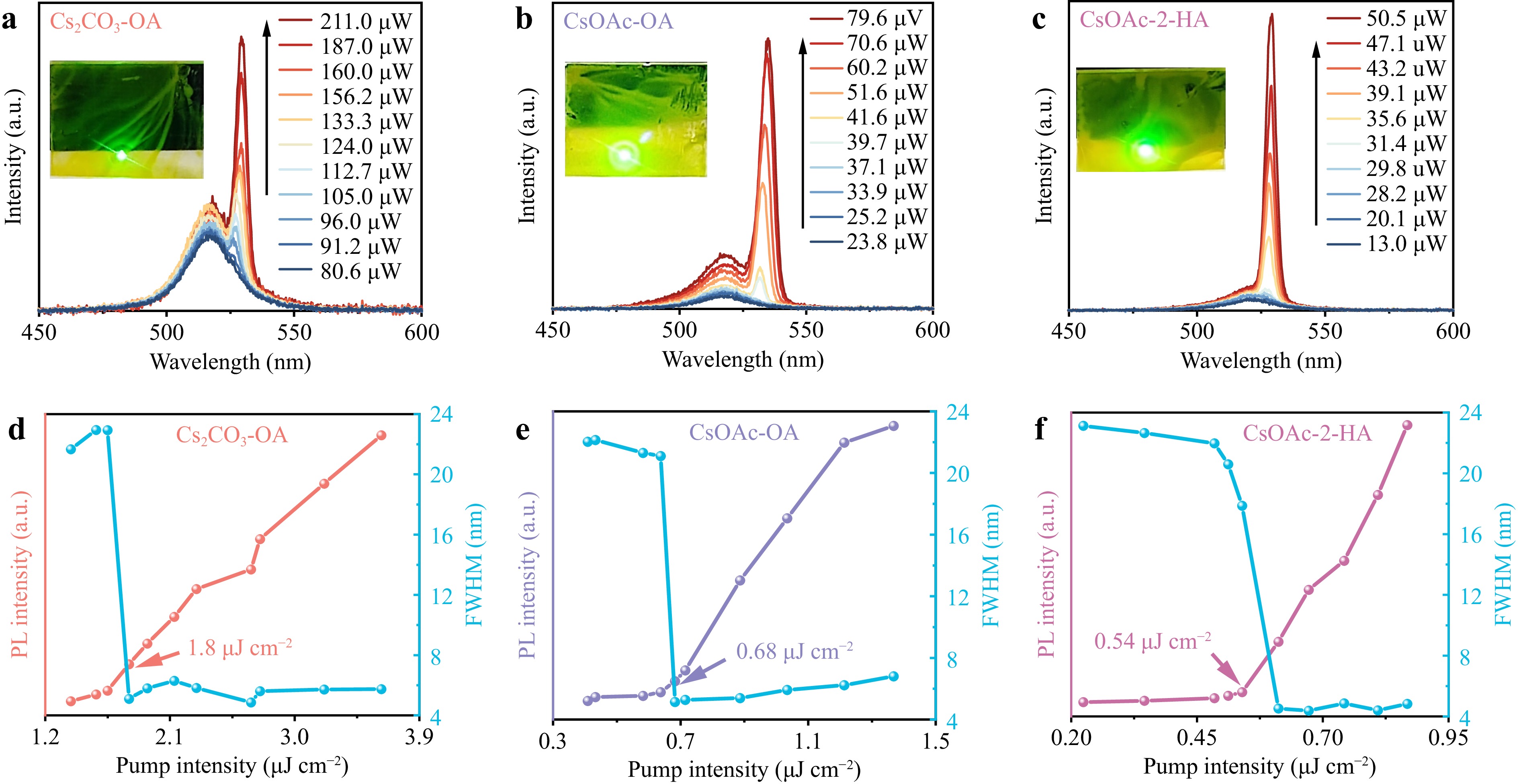

Considering the excellent stability and suppressed Auger recombination of the QDs, the ASE performance of the CsPbBr3 QDs was measured, and the ASE characteristics of these QDs were studied (Supplement Fig. S17). Fig. 5a-c show that under low-pump laser excitation, all the QDs exhibited broad spontaneous emission (SE) phenomena. With increasing pump density, new narrow ASE peaks appeared at 529, 534, and 529 nm for Cs2CO3-OA, CsOAc-OA, and CsOAc-2-HA QDs, respectively. Fig. 5d-f show that the FWHM of the Cs2CO3-OA, CsOAc-OA, and CsOAc-2-HA QDs present a sharp reduction, accompanied by a rapid increase in the emission intensity. As the pump density exceeded the threshold, the initial FWHM of these QDs was ~23 nm, which rapidly decreased to 4, 5, and 4 nm, respectively. A similar trend in the PL intensity was observed as a nonlinear process, indicative of the ASE phenomenon45. The ASE threshold for CsOAc-2-HA QDs is 0.54 μJ·cm−2, compared to 0.68 μJ·cm−2 and 1.8 μJ·cm−2 for CsOAc-OA and Cs2CO3-OA QDs, respectively. The photostability of these QDs under 1.2Pth pump laser excitation is shown in Supplement Fig. S18. The QDs obtained using AcO− with a low laser threshold exhibited enhanced stability and fewer surface defects. More importantly, 2-HA in conjunction with AcO− further enhanced the stimulated emission performance of QDs by reducing Auger recombination, beyond the effect of AcO− alone. Compared with advanced perovskites reported in the literature, the CsOAc-2-HA QDs exhibited excellent performance with the lowest ASE threshold, as presented in Supplement Table S5. Therefore, the CsOAc-2-HA QDs facilitate the realization of low-threshold lasers. Furthermore, perovskite QDs sandwiched between two distributed Bragg reflector (DBR) mirrors were utilized as surface-emitting random lasers to investigate laser performance. The results showed an apparent improvement in laser performance based on CsOAc-2-HA QDs46 (further discussed in Supplement Figs. S19 and S20), thus highlighting the significant potential of CsOAc-2-HA QDs in laser applications.

-

In this study, aiming to address challenges in conventional perovskite synthesis recipes, we developed a useful modified cesium precursor recipe that involved a dual-functional AcO− coupled with a short branched-chain ligand 2-HA. The successful synthesis of CsPbBr3 QDs exhibited some advantages, such as high stability, batch-to-batch uniformity, low Auger recombination, and a low ASE threshold. In addition, the influence of the conversion efficiency of Cs2CO3 and CsOAc to CsOL at different temperatures on the uniformity and optical properties of the QDs was systematically investigated, with the results indicating that the AcO− ligand could accelerate the conversion of the cesium salt. Thus, the purity of the cesium precursor could be improved by decreasing by-product formation during the reaction, particularly at room temperature, resulting in improved homogeneity and reproducibility. Furthermore, carrier dynamics analysis indicated that AcO− can act as a surface ligand to passivate the surface defects of the QDs, thus significantly reducing the requirements of the hot injection method for perovskite fabrication. The TA spectra and theoretical calculations showed that 2-HA exhibits a stronger binding affinity toward the QDs and can reduce the $ {E}_{\mathrm{B}} $ of the QDs, which can further passivate surface defects and effectively suppress biexciton Auger recombination, thereby improving the spontaneous emission rate of QDs. Consequently, compared with that of Cs2CO3-OA QDs, the ASE threshold of the CsOAc-2-HA QDs decreases by over 70% from 1.8 μJ·cm−2 to 0.54 μJ·cm−2, representing the lowest ASE threshold reported to date for QD-based ASE.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52302171), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (ZR2023QF005), Heilongjiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LH2023F026, LH2020A007, and LH2020F027), New Era Longjiang Excellent Doctoral Discovery Project (LJYXL2022-003), Teaching Reform Research Project of Harbin Engineering University (79005023/013), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3072024XX2606, 3072022TS2613, 79000012/012).

High-quality perovskite quantum dots with excellent reproducibility and amplified spontaneous emission by optimization of cesium precursor

- Light: Advanced Manufacturing , Article number: (2025)

- Received: 10 June 2024

- Revised: 05 December 2024

- Accepted: 22 December 2024 Published online: 05 March 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.37188/lam.2025.012

Abstract: Lead halide perovskite quantum dots (QDs) suffer from frequent batch-to-batch inconsistencies and poor reproducibility, resulting in serious non-radiative defect-assisted recombination and Auger recombination. To overcome these challenges, in this study, CsPbBr3 QDs were prepared by designing a novel cesium precursor recipe that involved a combination of dual-functional acetate (AcO−) and 2-hexyldecanoic acid (2-HA) as short-branched-chain ligand: first, AcO− aided in significantly improving the complete conversion degree of cesium salt, enhancing the purity of the cesium precursor from 70.26% to 98.59% with a low relative standard deviation of size distribution and photoluminescence quantum yield (9.02 and 0.82%, respectively) by decreasing the formation of by-products during the reaction, which leads to enhanced homogeneity and reproducibility, especially at room temperature. Second, AcO− can act as a surface ligand to passivate the dangling surface bonds. Furthermore, compared to oleic acid, 2-HA exhibited a stronger binding affinity toward the QDs, further passivated the surface defects, and effectively suppressed biexciton Auger recombination, thereby improving the spontaneous emission rate of the QDs. Consequently, the QDs prepared using this new recipe exhibited a uniform size distribution, a green emission peak at 512 nm, a high photoluminescence quantum yield of 99% with excellent stability, and a narrow emission linewidth of 22 nm. In particular, the optimized QDs exhibited enhanced amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) performance, while the ASE threshold of treated QDs reduced by 70% from 1.8 μJ·cm−2 to 0.54 μJ·cm−2.

Research Summary

Perovskite synthesis: Excellent reproducibility and low threshold quantum dots

The perovskite synthesis for high-quality quantum dots (QDs), which is obtained through chemical reaction of materials, including cesium precursors and organic ligands, is a prerequisite to ensure excellent ASE properties. A novel cesium precursor recipe that involved a dual-functional AcO- coupled with a short branched-chain ligand 2-HA has been developed by Mr. Liang Tao, Prof. Cheng-Hao Bi, and Prof. Wen-Xin Wang from Harbin Engineering University, China. The optimized CsPbBr3 QDs outperform existing lead halide perovskite QDs due to greatly increased stability, batch-to-batch uniformity, and optical performance. The researchers minimized the amplified spontaneous emission threshold by controlling the biexciton Auger recombination. The excellent homogeneity and reproducibility of CsPbBr3 QDs obtained from abundant experiment make this modified cesium precursor synthesis recipe more stable and controllable, which is essential to achieve industrialized goals for perovskites.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article′s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article′s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: