-

Melanoma tumor is one of the most complex types of neoplasms in the field of clinical oncology. For cases of metastasizing melanoma (stages 3-4), the 5-year survival rate of patients after the removal of tumor sites is not higher than 70%1. Approximately 35 years ago, melanoma was considered relatively uncommon. Currently, the global predicted number of new cases of melanoma from 2022 to 2025 is around 6.7%2. On average, up to 236,0003 new melanoma cases are diagnosed worldwide each year. Given the rapid metastatic potential of melanoma, about 40%4 of patients cannot be saved due to delayed diagnosis, whereas early detection allows for a 90%5 cure rate.

Since malignant melanomas have a pronounced tendency to metastasize, active drug targeting strategies are particularly valuable. These strategies enhance the concentration of therapeutic agents, including nanoparticles (NPs), at the tumor site6, at the same time sparing healthy tissues. There is a promising approach leveraging the α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (αMSH) and its interaction with the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), which is overexpressed in melanoma cells. The αMSH/MC1R signaling axis plays an important role in melanoma cell proliferation and migration7. The abundance of MC1R receptors on melanoma cells, ranging from several hundreds to several thousand per cell8–10, makes it an attractive target for drug delivery strategies. Various αMSH-modified formulations have been explored for tumor therapy, including conjugates with alpha- and beta-emitters11–13, cytotoxic drugs14,15, and photosensitizers16, as well as polymeric NPs for cytotoxic gene delivery17.

Among different types of nanomaterials, plasmonic NPs stand out as efficient converters of light to heat, which makes them suitable for use in photothermal therapy (PTT)18. PTT employs light-sensitive nanomaterials capable of generating heat upon exposure to light, and it is recognized as an effective, minimally invasive method for treating primary tumors19. This approach enables targeted delivery of photothermal agents and uses minimally invasive light techniques to precisely manage hyperthermia, minimizing damage to nearby healthy tissues. Interestingly, apart from direct thermal destruction of cells , the hyperthermia induced by PTT can stimulate dying tumor cells to release antigens, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and other immunogenic substances, thus enhancing the immune system activation20. There are several clinical trials using Au NPs as photothermal agents, which were summarized in Table S4. It is also worth highlighting that despite existing clinical studies, wider investigation of Au NPs implementation as heating agents for PTT is highly demanded.

In PTT, light-induced hyperthermia is the main mechanism responsible for cellular damage, leading to different outcomes: (i) programmable cell death through apoptosis at temperatures below 45 °C, or (ii) uncontrolled cell death through necrosis at temperatures above 48−50 °C21. As a consequence, there are two categories of PTT used in clinics: moderate-temperature hyperthermia (40−45 °C for 15−60 min) and high-temperature thermal ablation (above 50 °C for 4−6 min)22. The extent of thermal damage ultimately depends on the rate of temperature increase and the heating duration, which, in turn, are affected by the quantity of introduced photoresponsive agents, the applied laser power density, and the laser irradiation mode (either pulsed or continuous wave). Thus, to achieve efficient and predictable PTT, it is crucial to finely tune various parameters.

Taking into account previous studies on MSH-modified Au NPs and their biodistribution in melanoma tumor-bearing mice23,24, we performed a comparable investigation of the therapeutic performance of plasmonic NPs to reveal factors affecting efficiency of PTT. For this purpose, we have designed targeted photothermal agents based on Au nanorods (Au NRs) as a robust and safe nanotool for treatment of malignant melanoma (Scheme 1). We further covalently modified them with two types of MC1R agonistic peptides: (i) Ас-SYSMEHRWGKPV-NH2 (Ac-12), which closely mimics the αMSH sequence, and (ii) GKRKGSGSSIISHFRWGKPV-CONH2 (GKR), which incorporates a specific sequence with affinity to MC1Rs (shown in bold) and an additional fragment (shown in italics) with two primary amino groups to enhance functionalization rate of PEG-COOH-coated Au NRs. We have rigorously investigated the structural parameters of the obtained Au NRs, including PEGylated and modified with targeting peptides (Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR) as well as non-targeted counterparts (Au@PEG). Then, we theoretically and experimentally compared the heating abilities of Au@PEG irradiated in different pulsed regimes: either with a femtosecond (FS) laser at λ = 1030 nm, 200 kHz or a nanosecond (NS) laser at λ = 1064 nm, 100 kHz, highlighting the underlying physical mechanisms affecting Au NRs heating. Further, photoacoustic imaging was employed to compare the difference in the in vivo distributions of targeted Au NRs with different coatings (Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR) depending on the affinity between the ligand and the targeted tissue after Au NRs intravenous administration in mice with induced melanoma tumors. Finally, PTT was performed after systemic administration of either Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR, using either FS or NS laser irradiation. We present a thorough theoretical analysis and experimental investigation of how essential factors such as tumor accumulation of Au NRs and variations in laser irradiation modes influence the PTT outcomes. We anticipate that the insights gained in this research will advance the clinical application of functional plasmonic nanomaterials.

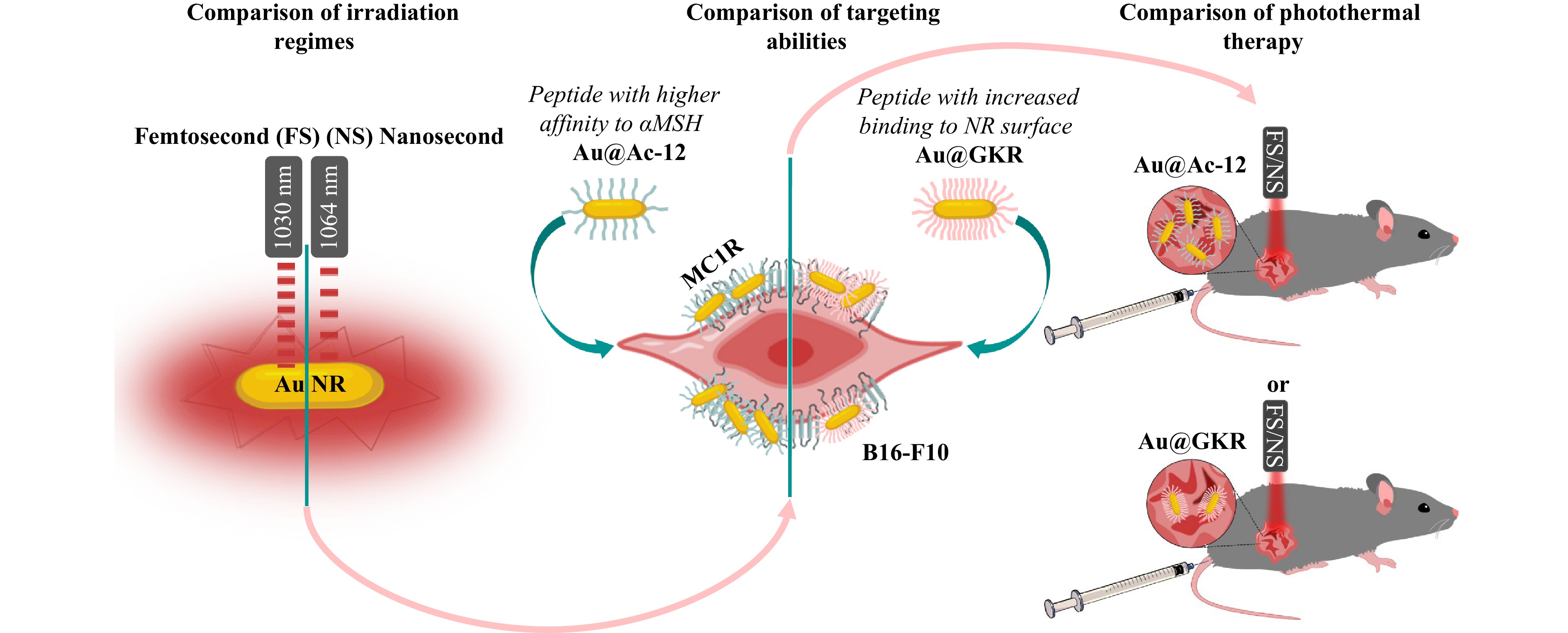

Fig. 1 Milestones of the study, which include (i) theoretical and experimental comparison of the heating abilities of Au NRs under irradiation with either a femtosecond (FS) or nanosecond (NS) pulsed laser; (ii) comparison of the targeting abilities of Au NRs modified either with Ac-12 peptide, possessing a high affinity to αMSH, or with GKR peptide with enhanced presence on the Au NRs’ surface, (iii) comparison of photothermal therapy using targeted Au NRs modified either with Ac-12 peptide (Au@Ac-12) or with GKR peptide (Au@GKR) and irradiated with either FS or NS.

-

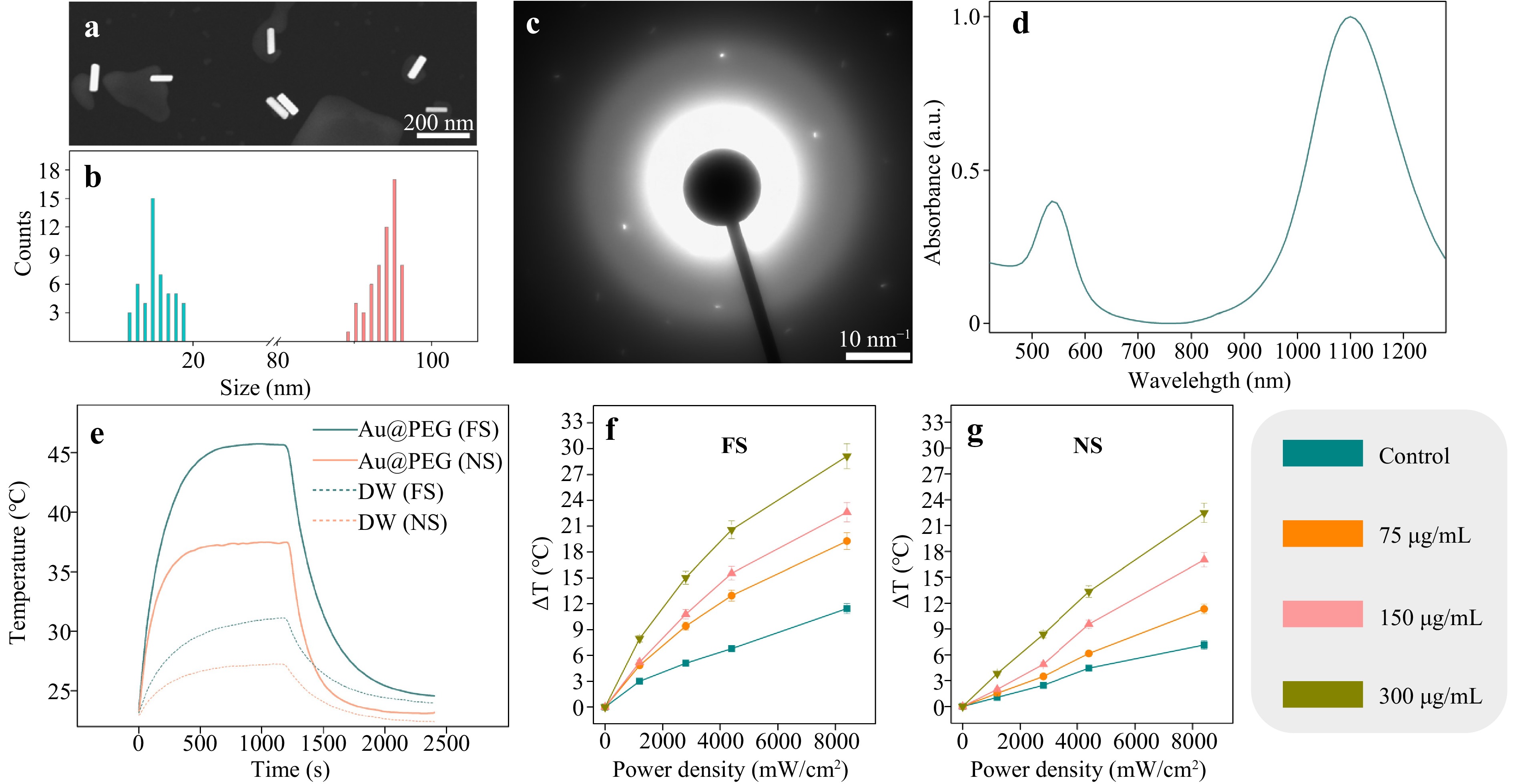

Photothermal agents based on Au NRs were synthesized using a seed-mediated approach25. The obtained Au NRs were further stabilized with PEG via ligand exchange to prevent their aggregation in biological environments (Au@PEG). The average length of the obtained Au NRs was 95 ± 3 nm, and their average width was 15 ± 4 nm, as derived from scanning and transmission electron microscopy images (Fig. 1a, b). A fast Fourier transform pattern confirms the crystallinity of the obtained Au NRs with an interplanar distance of 2.315 Å in agreement with the (100) direction of cubic Au26 (Fig. 1c, S4). The obtained Au@PEG possess two pronounced absorption bands at 1100 nm and 537 nm, which correspond to longitudinal and transverse bands, respectively (Fig. 1d). The rate of surface modification of Au NRs with PEG was evaluated using a method described elsewhere27, based on the formation of a complex with barium chloride and iodine solution. The modification extent of Au NRs’ with SH-PEG-COOH was found to be 99.4% (Fig. S2, Table S1).

Fig. 1 Сharacterization of Au@PEG. a Representative scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of Au@PEG in the backscattered-electron mode. b Size distributions of the length and width of Au@PEG as derived from SEM images. c X-ray diffraction pattern from Au@PEG. d UV−vis spectrum of Au@PEG at a concentration of 150 μg/mL. e Time-dependent temperature change of either Au@PEG dispersed in water or water (DW, dotted line), both irradiated with either FS (1030 nm) or NS (1064 nm). Au@PEG were irradiated for 1200 s, and then the laser was turned off. f Temperature increases for different concentrations of Au@PEG (75, 150, and 300 μg/mL) at different average FS laser power densities (0−8200 mW/cm2). g Temperature increases for different concentrations of Au@PEG (75, 150, and 300 μg/mL) at different average NS laser power densities (0−8200 mW/cm2).

To assess the heating abilities, the obtained Au NRs were dispersed in water in a quartz cuvette and irradiated with either an ytterbium fiber laser, Antaus Avesta (FS, λ = 1030 nm, f = 200 kHz, 4000 W/cm2), or another ytterbium fiber laser, IRE-POLUS ILMI-1-50 (NS, λ = 1064 nm, f = 100 kHz, 4000 W/cm2), for 20 min, and then the cuvette with Au@PEG was cooled down for 20 min. As controls, the same volume of water was additionally irradiated in the same modes (Fig. 1e). It has been previously shown that both CW and nanosecond pulsed PTT provide comparable results in B16-F10 melanoma inhibition28. However, pulsed lasers (especially femtosecond pulses) benefit from reduced heat-affected zone thus providing smaller damage to surrounding media. Therefore, it is important to compare nano- and femtosecond laser pulses for PTT efficiency. Under irradiation with FS, the aqueous colloid of Au@PEG dispersed in the quartz cuvette was heated up to 45 °C within the first 500 s, and further, the temperature reached a plateau. In the case of NS, the quartz cuvette with dispersed Au@PEG was heated up to 37 °C also within 500 s, and then the temperature reached a plateau. In both cases of irradiation scenarios (FS and NS), the temperature of water increased, but the obtained temperatures were lower than in the case of Au@PEG. These observations are also valid for heating of different concentrations of Au@PEG with FS and NS at different laser power densities (Fig. 1f, g). As previously, in the FS-pulsed regime, Au@PEG heated up more pronouncedly compared to the NS-pulsed regime. With increasing laser power density and concentration of Au@PEG, heat generation also increased by 29 °C (FS) and 22 °C (NS). Generally, the lower temperature generated by Au@PEG excited with NS is explained by NRs’ cooling, which happens on timescales less than 1 ns, and, therefore, heating of Au@PEG is slower. Importantly, there is a significant decay in temperature elevation observed for small NPs, which can be attributed to the rapid release of energy to the surroundings, especially in the NS-pulsed regime, in which diffusion plays a dominant role29. Additionally, photothermal conversion efficiency of Au@PEG was calculated and equal to 22.7% and 26.4% for FS and NS, respectively (Fig. S6). These values are in agreement with the previously published works30–32. Additionally, we checked reshaping of Au@PEG after irradiation with FS and NS (up to 8800 mW/cm2). As can be seen in Fig. S7, the aspect ratio values remain approximately constant (~6), but this parameter undergoes a slight decrease at the maximum density powers applied, which are greatly above the power densities used for the therapy. Notably, considering the maximal applied laser power density (8800 mW/cm2), the decrease in the aspect ratio (~5.5) falls into the favorable peak of absorbance for FS laser, as indicated in Fig. S1b.

-

To further explore the heating capabilities of Au@PEG, we numerically simulated the heating of an individual Au NR in water exposed to FS- and NS-pulsed irradiation. Note that since the thermophysical parameters of water are close to those of biological materials, we modeled the heating abilities of a Au NR dispersed in water under laser irradiation33. The calculations are based on the well-known two-temperature model (TTM) that describes the evolution of electron $ {T}_{e} $ and phonon $ {T}_{ph} $ temperatures in metal structures34,35. Initially, electromagnetic radiation is absorbed by the electron subsystem, leading to the formation of thermal electrons and an increase in the electron temperature $ {T}_{e} $. Subsequently, energy is transferred from the electron subsystem to the phonon (lattice) subsystem through electron-phonon scattering, resulting in a gradual increase of the phonon temperature $ {T}_{ph}, $ corresponding to the NR heating. Thus, our approach involves solving a self-consistent system of two differential equations describing the dynamics of temperatures, considering the electromagnetic field distribution within the NR under incident radiation:

$$\begin{split} {C}_{e}\frac{\partial {T}_{e} (\underline{r,}t)}{\partial t}=&\nabla [{k}_{e}\nabla {T}_{e}(\underline{r},t)]-{g}_{e-ph}({T}_{e}(\underline{r},t)-{T}_{ph}(\underline{r},t))+\\&Q(\underline{r},t) \end{split}$$ $$ {C}_{ph}\frac{\partial {T}_{ph}\left(\underline{r,}t\right)}{\partial t}=\nabla [{k}_{ph}\nabla {T}_{ph}(\underline{r},t\left)\right]+{g}_{e-ph}\left({T}_{e}\right(\underline{r},t)-{T}_{ph}(\underline{r},t\left)\right) $$ where $ {T}_{e} $ and $ {T}_{ph} $ are the temperatures of the thermal electron and phonon (lattice) subsystems, respectively; $ {C}_{e}=\gamma {T}_{e} $ is the electron heat capacity, where $ \gamma =71\;\rm J/{m}^{3}{K}^{2}; $ $ {C}_{ph}=310\;\rm J/kg{K}^{}\cdot \rho $ is the phonon heat capacity, where $ \rho =1930\;\rm kg/{m}^{3} $ is the density; $ {k}_{e}={k}_{0}{T}_{e}/{T}_{ph} $ is the electron thermal conductivity, where $ {k}_{0}=320\;\rm W/m{K}^{}; $ $ {k}_{ph}=310\;\rm W/m{K}^{} $ is the phonon thermal conductivity, and $ {g}_{e-ph}=2.3\cdot 1{0}^{10}\;\rm W/c{m}^{3}K $ is the rate of energy transfer between electrons and phonons. These data are provided for bulk gold36. In our calculations, we also take into account the heat outflow from the Au NR into the aquatic environment by choosing the following water properties: the thermal conductivity $ {k}_{water}=0.606\;\rm W/m{K}^{} $ and the heat capacity of water $ {C}_{\rm{water}}=4220\;\rm J/kg{K}^{}\cdot {\rho }_{water} $, where $ \rho_{water} =997\;\rm kg/{m}^{3} $ is the density37.

The heat source $ Q(\underline{r},t) $ is characterized by absorption at each point of the structure, and it depends on the metal permittivity in the following manner:

$$\begin{array}{c} Q(\underline{r},t)=\dfrac{1}{2}\omega Im\left[\varepsilon \right]{\varepsilon }_{0} < \left|\underline{E}\right(\underline{r},t){|}^{2} > \cdot GP(t),\\GP(t)=exp(-4\cdot ln2\cdot (t-{t}_{0}{)}^{2}/{\tau _{p}^{2}}) \end{array}$$ where $ GP\left(t\right) $ corresponds to a Gaussian pulse with the peak time $ {t}_{0} $ and the pulse duration $ {\tau }_{p}, $ and $ \left|\underline{E}\right(\underline{r},t){|}^{2} $is the squared norm of the electric field at each point of the particle. We average this quantity over all possible polarizations and angles of incidence of electromagnetic radiation with respect to the NR axes and obtain the following equation $ < \left|\underline{E}\right(\underline{r},t){|}^{2} > ={1}/{4}(|{\underline{E}}^{(1)}(\underline{r},t){|}^{2}+ |{\underline{E}}^{(2)}(\underline{r},t){|}^{2})+{1}/{2}|{\underline{E}}^{(3)}(\underline{r},t){|}^{2}, $ where $ {\underline{E}}^{(1,2,3)}(\underline{r},t) $ correspond to the field components along the main axes of the NR as illustrated in Fig. 2d (inset). The predominant contribution in the infrared range comes from the polarization aligned with the long axis of the nanorod $ {\underline{E}}^{\left(2\right)}(\underline{r},t $), exceeding those of other polarizations by several orders of magnitude. We considered plane wave incidence since the beam focusing was quite weak.

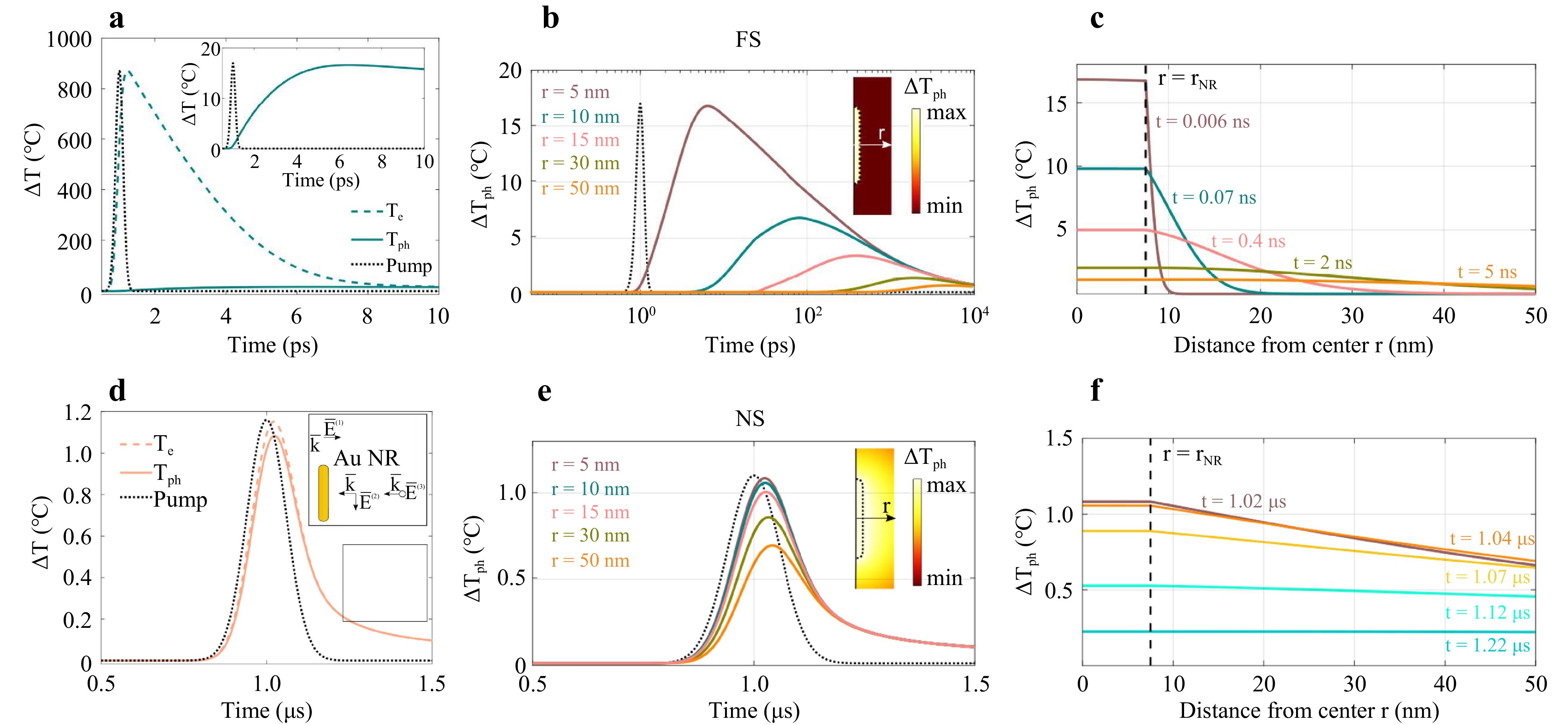

Fig. 2 Numerical simulation of temperature evolution within and around Au NR. a Dynamics of the phonon (solid curve) Tph and electron temperatures Te (dashed curve) averaged over the volume of a NR excited by the FS laser. The pulse profile is shown by the black dotted line. Inset: the phonon temperature at a smaller vertical scale, reaching about 17 K inside the NR. b Dependence of the temperature increase ΔTph on the distance (r = 5, 10, 15, 30, 50 nm) from the center of an Au NR with radium rNR = 7.5 nm suspended in water and excited with FS pulses. Pulse profile is shown by the dotted curve. Inset: temperature profile inside and outside the NR; the axis indicates the measurement direction of r. The temperature distribution corresponds to the time of maximal averaged temperature inside the NR. c Temperature distribution within and around the NR at various distances from its center r for different time values t and excited with FS. Curves corresponding to the times of maximal phonon temperature for different distances (r = 5, 10, 15, 30, 50 nm) from B are shown in the same color. d Dynamics of the phonon (solid curve) Tph and electron temperatures Te (dashed curve) averaged over the volume of a NR excited by the NS laser. The pulse profile is shown by the black dotted line. Inset: three distinct orthogonal polarizations $ {\underline{\mathrm{E}}}^{(\mathrm{1,2},3)}(\underline{\mathrm{r}},\mathrm{t}) $ with respect to the NR. These polarizations determine the average field inside the NR $ < |\underline{\mathrm{E}}(\underline{\mathrm{r}},\mathrm{t}){|}^{2} > $, positioned arbitrarily with respect to the incident irradiation. e Dependence of the temperature increase ΔTph on the distance (r = 5, 10, 15, 30, 50 nm) from the center of an Au NR with radium rNR = 7.5 nm suspended in water and excited with NS pulses. Pulse profile is shown by the dotted curve. Inset: temperature profile inside and outside the NR; the axis indicates the measurement direction of r. The temperature distribution corresponds to the time of maximal averaged temperature inside the NR. f Temperature distribution within and around the NR at various distances from its center r for different time values t and excited with NS. Curves corresponding to the times of maximum phonon temperature for different distances (r = 5, 10, 15, 30, 50 nm) from E are shown in the same color.

Thermal boundary conditions were specified based on the linear relationship between the heat flux density through the computational domain’s surface and the temperature change at the boundary $ g={{k}_{water}}/ {{R}_{out}}(T-{T}_{0}) $, where $ {T}_{0}=300\;K $ is the room temperature38.

The absorption spectrum of a Au NR suspended in water is shown in Fig. S1A for varying aspect ratios $ l/w $, where $ l $ is the NR’s length and $ w $ is its width. The calculated absorption results are in good agreement with the experimental ones (Fig. 1d). Indeed, the variability in the geometric parameters of the rod demonstrated in Fig. 1b accounts for the broadened absorption resonance observed in experiments. When the aspect ratio increases, the resonance shifts towards longer wavelengths.

Fig. 2 illustrates the temperature evolution of electron and phonon systems for FS and NS irradiation, averaged across the volume of a single NR. In the case of FS heating (Fig. 2a), initially, thermal electrons are rapidly heated. Subsequently, the electrons transfer energy to phonons over the timescale of electron-phonon scattering, leading to a gradual increase in the phonon temperature until a thermal equilibrium is reached, within approximately 10 ps.

Conversely, with NS heating, the energy transfer between the electron and phonon subsystems occurs much faster than the pulse duration (Fig. 2d). Consequently, both subsystems reach their peak temperatures nearly simultaneously on the timescale of the pulse. The key distinction lies in the relaxation rates of the electron and phonon temperatures. While the electron temperature relaxes through electron-phonon scattering, the phonon temperature within the NR dissipates into the surrounding water, resulting in different maximum temperatures of the subsystems.

Meanwhile, Fig. S1b reveals that NS irradiation is more resonant in terms of absorption for the characteristic aspect ratio of our particles (ranging from $ l/w=5.8 $ to 7). However, the calculations of the NR temperature indicate that FS radiation leads to a more efficient particle heating than NS radiation with the equivalent pulse fluence29. This phenomenon can be attributed to the rapid cooling of a single NR through heat dissipation into water, typically occurring in time periods shorter than 1 ns, making NS-pulse heating too slow for achieving maximum temperature elevation similar to that observed with FS irradiation.

Although FS heating within a particle is significantly more intense than the NS one, outside the particle, the maximum achievable temperature drops more rapidly with distance from the particle $ r $. This is illustrated in Fig. 2b, e, showing the temperature dynamics as a function of distance from the particle center. For instance, the orange line in Fig. 2b, c indicates temperature at the time t = 5 ns, at which the maximum phonon temperature was reached at the point r = 50 nm away from NR center during FS excitation. Notably, approximately 50 nm away from the NR center, the maximum temperatures achievable under both FS and NS excitation become comparable, at around $ \Delta {T}_{ph}=0.6 $°C. Indeed, FS heating results in a more distinct temperature distribution profile as it takes nanoseconds to transfer heat to the NR surrounding (Fig. 2c, f).

The main conclusion from the numerical simulation part is that irradiation with FS-pulsed heating generates more heat not only in the NR but also in its surrounding environment, compared to NS heating, although this effect is observed over much shorter timescales. In the case of aggregation of several NPs in biological environments, plasmon coupling39 occurs after endocytosis40, thereby affecting the heating process. The overall photothermal performance of the assembled NPs is based on their collective heating ability and the plasmon coupling effect41. In the case of collective simultaneous irradiation of several NPs, cumulative temperature contributions can cause high and uniform temperatures42, which can compensate for the lower heating due to the shift of the absorbance band in the aggregation state of the particles.

-

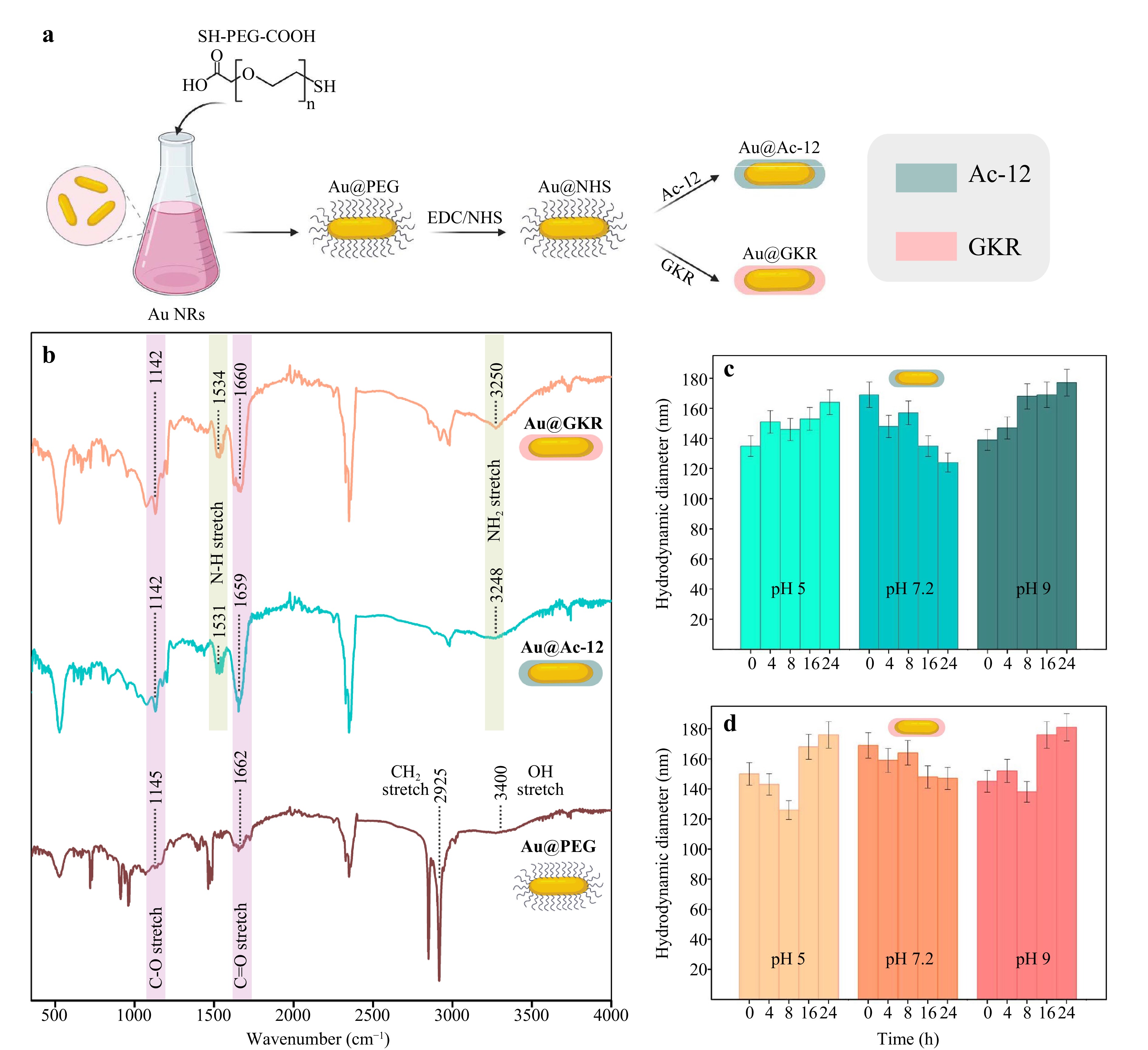

To impart targeting properties to Au@PEG NRs, the NRs were covalently modified with two different peptides: (i) Ac-SYSMEHRWGKPV-CONH2 (Ac-12), and (ii) GKRKGSGSSIISHFRWGKPV-CONH2 (GKR). A detailed description of the used peptides is provided in Supporting Information. Briefly, Ac-12 peptide closely mimics the αMSH sequence, ensuring strong binding to MC1R, while GKR incorporates a specific sequence (in bold) with fewer affinity to MC1Rs43 and an additional linker (in italics) enriched with free primary amino groups to achieve superior conjugation extent to PEGylated Au NRs. Therefore, here we aimed to investigate what is more beneficial for the PTT: better affinity of peptides to melanoma-specific receptors or increased amount of peptides on the surface of NRs. To conjugate Au@PEG with both peptides, the EDC/NHS chemistry process was applied. First, 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) was added to a solution of Au@PEG to catalyze the formation of amide bonds between the carboxyl groups of PEG and peptide amine groups. In addition, N-hydroxy sulfosuccinimide (NHS) was added to increase the stability44 of coupling between functional groups. Next, Ac-12 or GKR peptides were added to Au@PEG with activated surfaces, which led to the formation of Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR complexes (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3 Functionalization of Au@PEG with peptides. a Scheme of Au@PEG functionalization. b Fourier transform IR spectra of Au@PEG, Au@Ac-12, and Au@GKR. c Time dependence of the hydrodynamic diameter of Au@Ac-12 on the pH of the buffer solution. d Time dependence of the hydrodynamic diameter of Au@GKR on the pH of the buffer solution. The graphic was prepared using modified art elements from www.biorender.com.

To verify the successful functionalization of Au NRs with PEG, Ac-12, and GKR, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) analysis was performed (Fig. 3b, S5). The terminal COOH-groups of PEG molecules could be directly identified through C–O, С=О and O–H bonds. Fig. 3b shows the FTIR spectrum of Au@PEG, with bands at 1145, 1662, and 3400 cm–1 related to C–O, C=O, and O–H bonds, respectively45. The broad and weak absorption band at 3400 cm−1 originates from the O–H group participating in intermolecular hydrogen bonds. The absence of an absorption band in the region of 2600−2550 cm−1 can be explained by the S–H bond breaking in the PEG molecule, which led to the formation of a new bond, i.e. S–Au bonds46. This confirms that the PEG molecules are bound to the Au surface through an S–Au bond at one end, and COOH- groups are freely present at the other end of PEG. In the FTIR spectrum of Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR, there is a broad peak centered at 3250 cm−1, which indicates the presence of primary amine groups of peptide molecules, and an absorption band in the region of 1530 cm−1, characteristic of a primary amine, which are of interest with N–H stretching. In the Au@PEG spectra, there are no peaks in these regions, indicating successful conjugation of Ac-12 and GKR peptides onto the surface of Au NRs.

Surface functionalization with peptides (% w/w) was determined using a previously described colorimetric method based on the detection of unreacted primary amines in peptides47 with fluorescamine (Fig. S3). As expected, the functionalization ratio of Au@GKR was slightly higher than Au@Ac-12 resulting in 4.5% versus 1.8%, respectively. The zeta potential of the functionalized Au NRs (Table S2) became slightly more neutral (−0.69 mV and −1.37 mV for Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR versus −14 mV for Au@PEG, respectively), which indirectly indicates successful peptide conjugation.

Colloidal stability of the Au NRs coated with different peptides (Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR) was tested in sodium phosphate buffer at different pH values (pH = 5, pH = 7.2, and pH = 9) and at different time points (0, 4, 8, 16, and 24 h). Evolution of the hydrodynamic size of the particles was measured with a dynamic light scattering approach (Fig. 3c, d). According to the obtained data, the hydrodynamic diameters of both types of peptide-coated Au NRs (Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR) remain approximately constant, indicating their good colloidal stability in the tested buffers at different pH values.

-

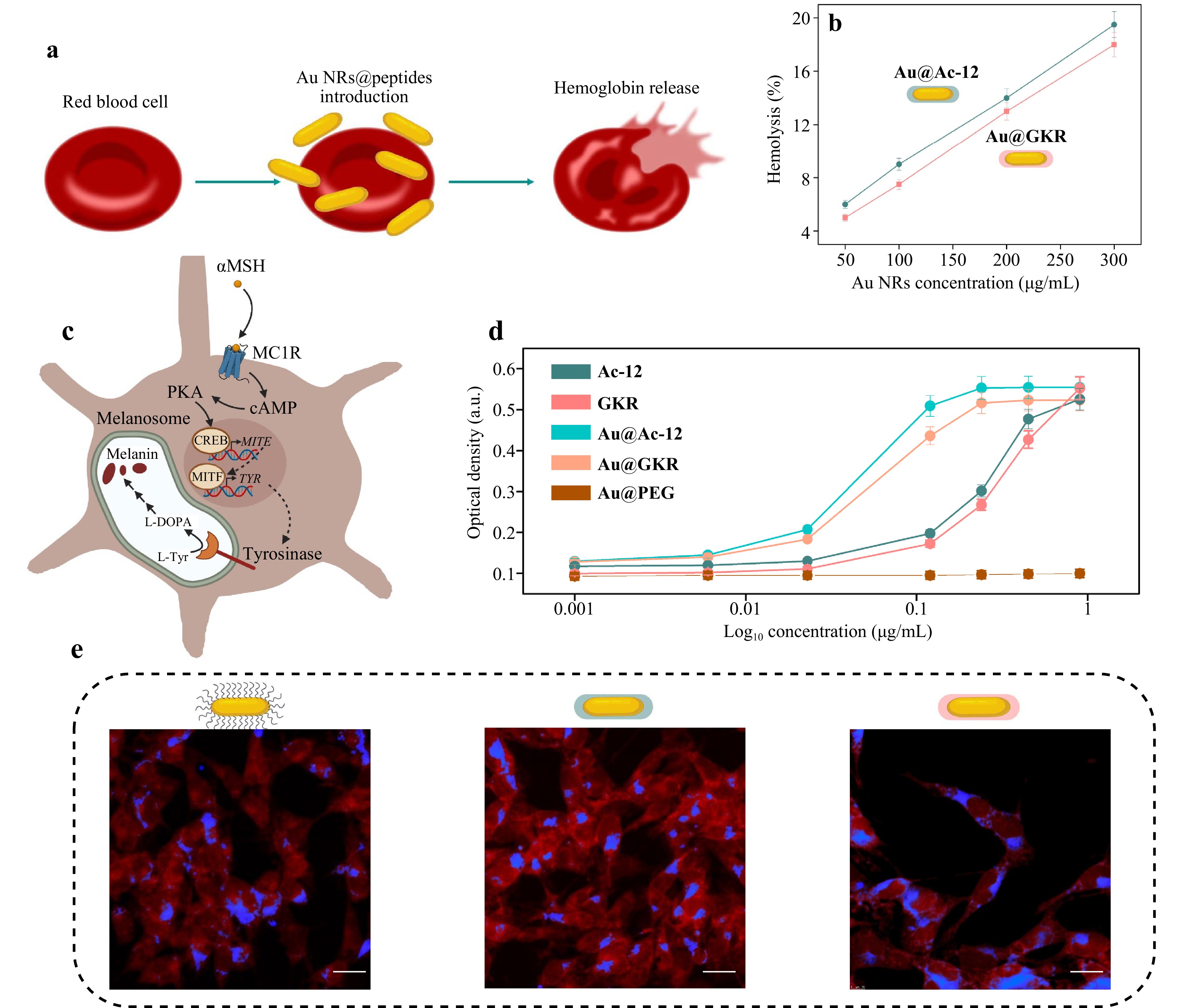

To assess the blood biocompatibility of the obtained Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR, hemolysis assay was performed. Generally, hemolysis assay evaluates hemoglobin release in the plasma, which is an indicator of red blood cells damage, in our case, in response to NRs exposure48 (Fig. 4a, S9). To assess this, peptide-coated Au NRs (Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR) were added to isolated erythrocytes at different concentrations in the range from 50 to 300 μg/mL and incubated for 2 h. PBS and lysis buffers were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Based on the obtained data, hemolysis level increases in a dose-dependent manner with increasing concentration of added Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR. Notably, the hemolysis level remained the same, regardless of the Au NRs’ coating (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4 Interaction of targeted Au NRs with cells in vitro. a Schematic illustration of red blood cell damage. b Relative rate of hemolysis in human red blood cells upon incubation with a suspension of Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR at different concentrations (50−300 µg/mL). c Schematic illustration of the proposed mechanism of melanin production in response to MC1R stimulation. PKA: protein kinase A; CREB: cAMP response element-binding protein; MITF: microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; TYR: tyrosinase; TYRP1: tyrosinase-related protein 1; L-DOPA: L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine. d Production of melanin as a function of Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR concentration; free Ac-12 and GKR, and Au@PEG were added at the same concentrations and used as controls. e Representative CLSM image of B16-F10 cells associated with (from left to right) Au@PEG/Au@Ac-12/Au@GKR labeled with Cy5 (blue fluorescence), after incubation for 24 h. B16-F10 cells were stained with Rhodamine B (red fluorescence). Scale bars correspond to 30 µm.

To ensure ligand availability in Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR, melanogenesis assay was carried out. This test relies on tyrosinase upregulation and melanin production in response to MC1R stimulation with agonists49 (Fig. 4c). Production of melanin was tested using B16-F10 cells after their treatment with free peptides and functionalized Au NRs. Both Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR showed the ability to cause concentration-dependent receptor-mediated melanogenesis, suggesting that their ligand moiety can access the melanocortin receptors (Fig. 4d). Noteworthy, both types of NRs caused similar effects, which were superior to those of the free Ac-12 and GKR peptides, according to the obtained EC50 values: 0.046 µg/mL for Au@Ac-12 versus 0.281 µg/mL for Ac-12, and 0.058 µg/mL for Au@GKR versus 0.304 for GKR (Table S3). This difference could result from the Au NRs’ precipitation on the cell monolayer and increased local agonist concentration.

Additionally, to visualize the interaction of Au@Ac-12, Au@GKR, and Au@PEG with B16-F10 cells, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) was performed. For this, Au NRs with different coatings were fluorescently labeled with Cy5 and incubated with B16-F10 cells for 24 h. Afterwards, the cell membranes were stained with Rhodamine B (RhB) and imaged with CLSM (Fig. 4e). According to the obtained CLSM images, no significant difference in the cell-NR association was revealed. A three-dimensional CLSM image (Fig. S10) of a scanned cell with internalized Au@Ac-12 visualizes cell-NR interaction in the x-y section at a given z-location. The two smaller panels visualize the side views of a stained cell along the x–z (top panel) and y–z cross sections (right-side panel). According to this, NRs were mostly located inside the cells, presumably due to receptor-mediated uptake by MC1R-expressing melanoma cells.

-

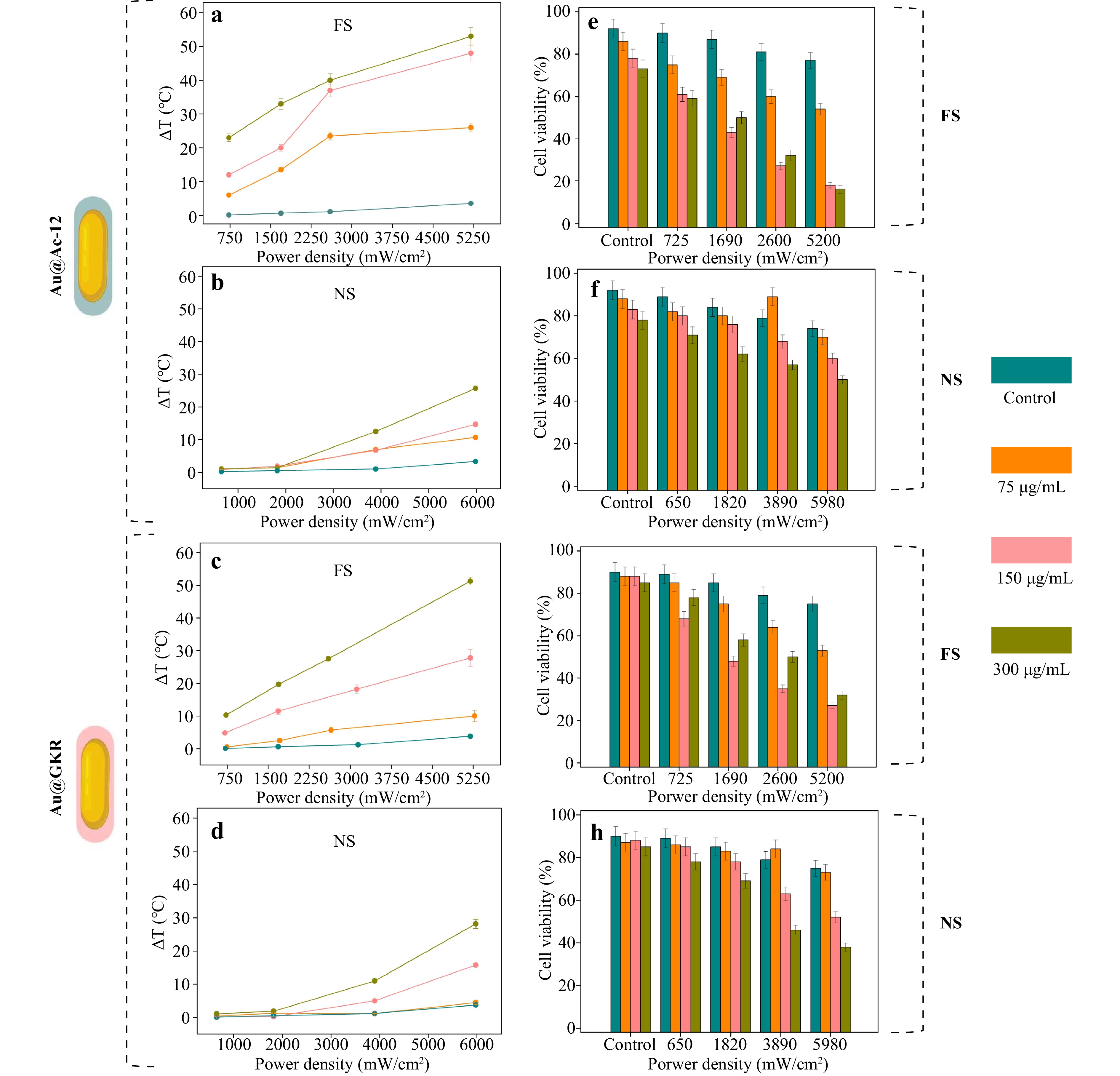

To check the heating abilities of Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR in association with cells, Au NRs with different coatings were added to B16-F10 cells at different concentrations (75, 150, and 300 g/mL) and incubated for 24 h (Fig. S11). Further, after thorough washing, cells were irradiated with either a femtosecond pulsed (FS, 1030 nm) or a nanosecond pulsed (NS, 1064 nm) laser at different laser power densities (from 725 ± 20 to 5200 ± 50 mW/cm2 for FS; from 650 ± 15 to 6000 ± 20 mW/cm2 for NS) for 3 min for each sample. The temperature increase was monitored with a thermal camera, and additionally, the cell viability was evaluated using AlamarBlue assay. According to the obtained data, no significant difference between Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR in terms of their heating abilities and, consequently, in cell viability was detected, which is in agreement with the CLSM images. This means that despite the possible differences in their attachments to the cell membranes, a fraction of Au NRs was presumably attached to the cell plasma membranes due to electrostatic interaction and gravitational force, mitigating the possible differences in specific cell-NRs bindings. Therefore, the generated heat was released in a similar way, leading to identical dose-dependent cell viability: an increase either in the applied laser power density or in the amount of added NRs resulted in decreasing cell viability (Fig. 5). Nonetheless, irradiation of cells with Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR with either FS or NS at the same laser power density led to different heating outcomes, similarly to heating outside cells (Fig. 1f, g). Analogously, FS irradiation of cells associated with Au NRs led to higher temperatures compared to NS irradiation. At the maximum used laser power density (5200−6000 mW/cm2), temperature difference (ΔT) increased up to 50 ± 3 °C under FS irradiation, and to 30 ± 5 °C under NS irradiation. As mentioned, lower temperatures under NS irradiation can be explained by the rapid cooling of NRs through the dissipation into aqueous cellular environment, and, therefore, slower heating of NRs associated with cells, as confirmed by our numerical simulation data (Fig. 2). As expected, a higher heat release led to a lower percentage of B16-F10 viability, which, in the case of FS irradiation (5250 mW/cm2) and at 300 μg/mL of added Au@Ac-12, equals to 16 ± 5%; and at 300 μg/mL of added Au@GKR, to 32 ± 5%. In the case of NS irradiation (5980 mW/cm2) and at 300 μg/mL of added Au NRs, the percentage of viable cells equals 50 ± 5% for Au@Ac-12, and 38 ± 5% for Au@GKR.

Fig. 5 Heating abilities of targeted Au NRs associated with B16-F10 cells in vitro. Temperature increases for different concentrations of Au NRs (75, 150, and 300 μg/mL) added to B16−F10 cells and irradiated with laser at different average power densities (up to 6000 mW/cm2): a Au@Ac-12, FS; b Au@Ac-12, NS; c Au@GKR, FS; d Au@GKR, NS. Viability of B16−F10 cells incubated with Au NRs added at different concentrations (75, 150, and 300 μg/mL) and irradiated with laser at different average power densities (up to 6000 mW/cm2): e Au@Ac-12, FS; f Au@Ac-12, NS; g Au@GKR, FS; h Au@GKR, NS.

Thus, we further proceeded with both Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR: they were intravenously administered into B16-F10 tumor-bearing mice at an amount higher than those used for in vitro tests: 100 μg (100 μL), since only a small part of the intravenously injected NRs will reach the tumor.

-

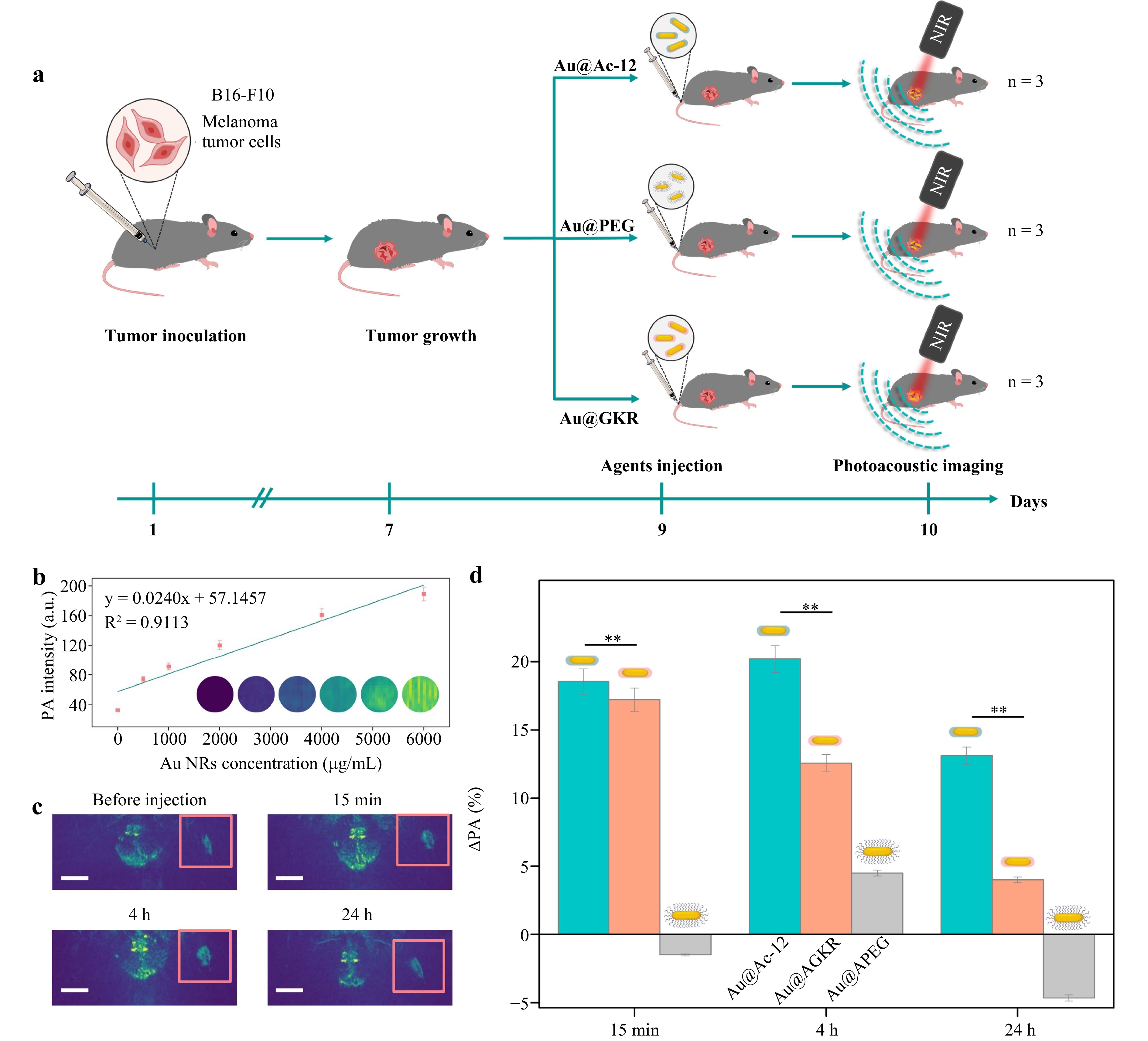

Au NRs provide a strong absorption of NIR light, which is essential for both PTT and photoacoustic imaging. Generally, photoacoustic imaging involves illuminating photoresponsive agents, which then absorb the light energy and convert it into heat. This heat generation causes a thermoelastic expansion, producing acoustic waves, which can be detected. The scattering of sound is significantly lower compared to light (a thousand times lower), which allows acoustic signals to travel farther in biological tissues, enhancing the imaging depth and clarity50. Notably, in living organisms, hemoglobin51,52 and melanin53 have the most pronounced photoacoustic signals. In other words, blood vessels and areas of skin with increased pigmentation can be visualized using a photoacoustic imaging system. At the same time, the introduction of objects with photoacoustic contrast into the body leads to an increase in the photoacoustic signal intensity in the area of accumulation of such objects compared with the endogenous photoacoustic signal.

Before the in vivo imaging, photoacoustic properties of Au@PEG were studied. For this, phantoms with different concentrations of Au NRs (500−6000 μg/mL) were created and imaged using a TriTom (PhotoSound Technologies, Inc., USA) imaging platform with a PhotoSonus (Ekspla, Lithuania) pulsed laser (wavelength 1064 nm, pulse energy 80 mJ). Overall, the laser power density of the photoacoustic imaging system is approximately an order of magnitude lower than that is usually used in therapy. Au@PEG samples provided a pronounced photoacoustic signal, which increased with increasing concentration of the Au NRs (Fig. 6b, S8).

Fig. 6 In vivo photoacoustic imaging of targeted Au NRs. a Scheme of bioimaging experimental procedure. b Photoacoustic (PA) signal of Au@PEG phantoms at different concentrations. c Photoacoustic scans of melanoma in mice before and after the injection (15 min, 4 h, and 24 h) of 100 µL, 1000 µg/mL of Au@Ac-12. Scale bar corresponds to 1 cm. d Rise of PA signal (ΔPA, %) 15 min, 4 h, and 24 h after the intravenous injection of 100 µL, 1000 µg/mL of Au@PEG, Au@Ac-12, and Au@GKR (the symbol ** indicates p < 0.01). The number of animals used was n = 3 for each group. The graphic was prepared using modified art elements from Servier Medical Art, found at https://smart.servier.com, used under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Then, to monitor tumor accumulation of the targeted Au NRs in vivo, Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR at concentrations of 1000 μg/mL (100 μg, 100 μL) were injected in the tail vein of melanoma tumor-bearing mice. As a control sample, Au@PEG was used (Fig. 6a). All the animal groups were visualized at different time periods: (i) before the injection, (ii) 15 min after the injection, (iii) 4 h after the injection, and (iv) 24 h after the injection. To assess the localization of peptide-coated Au NRs in a tumor at different time points, photoacoustic signal originating from the tumor before the injection of Au NRs was subtracted from a 100 × 100 pixel region containing the tumor area. By analyzing the pixel intensity density, we obtained data on the change of photoacoustic signal depending on the time after the nanoparticles’ injection into the body (Fig. 6c).

According to the obtained data, Au@Ac-12, which had the highest affinity to MC1R (overexpressed on the melanoma cell surface), were detected in the tumor area at the highest rate. Particularly, the highest accumulation of Au NRs was found 4 h post-injection (Fig. 6d). Interestingly, 24 h after the injection, the photoacoustic signal from Au@Ac-12 decreased, which can be attributed to two factors. First, this decrease in the photoacoustic signal54 could result from continuous rapid growth of melanoma tumor with melanin-producing cells. Second, a part of Au NRs that had been associated with tumor endothelium or interendothelial gaps soon after the injection could be gradually washed out later, as was demonstrated earlier for polymer-based nanoparticles modified with MC1R agonist peptides55,56. Notably, the peptide with a lower affinity to MC1R but a higher amount of −NH2 groups (Au@GKR) and, consequently, a higher coverage of Au NRs demonstrated a behavior similar to Au@Ac-12, but a lower accumulation in tumors. Therefore, although the amount of Ac-12 peptide attached onto the surface of Au NRs was lower compared to GKR, intratumoral localization of Au@Ac-12 was higher than that of Au@GKR, presumably, due to a higher affinity of Ac-12 to MC1Rs on the melanoma cell surface. Notably, change of PA signal depends only on the accumulation of Au NRs in the tumor, and it was not affected by biological environment and reshaping upon light irradiation (Figs. S7, S12).

The safety of Au NPs after intravenous delivery is a critical aspect of their potential clinical use. Studies have shown that Au NPs can accumulate in organs such as the liver, spleen, and kidneys, without inducing liver or kidney toxicity, as confirmed by the plasmatic ALT/AST activities as well as creatininemia values57. Although injected Au NPs can retain for a long time in tissues, no long-term toxicity (including any signs of histological damage or inflammation) of Au NRs in healthy tissues was observed within at least a 15-month term after photothermal tumor therapy (PTT)58.

Here, histological analysis of the main organs (the liver, lungs, kidney, spleen, and heart) and tumors was carried out to evaluate the safety of the intravenously and intratumorally injected NRs (Fig. S15). Note that histological analysis of the main organs was additionally performed after intratumoral injection to reveal possible pathological changes in tissues for different routes of Au NRs’ administration. Further, targeted therapy experiments were performed, using intravenous injection of the Au NRs. Generally, a control tumor sample contained predominantly spindle-shaped and polygonal cells, and an irregular distribution of melanin. Intravenous and intratumoral administration of Au@Ac-12, Au@GKR, and Au@PEG did not affect the tumor cell viability and integrity. After the administration of Au@Ac-12, Au@GKR, and Au@PEG, no inflammatory reactions, cytotoxicity effects, or protein aggregates with the investigated Au NRs were detected in the liver tissue samples. The lung samples had intact terminal bronchioles and sinuses. The walls of the terminal and respiratory bronchioles had a single-layer cuboidal ciliated epithelium, a weakly pronounced muscular plate, and a thin layer of loose connective tissue. The alveolar walls comprised a single-layer squamous epithelium and an interalveolar septum with blood capillaries with no signs of damage. In the observed spleen tissues, the capsule and trabeculae of dense fibrous connective tissue, smooth myocytes, red and white pulp cells, numerous blood vessels, and blood cells were normal. In the kidney samples, the obtained Au@Ac-12, Au@GKR, and Au@PEG did not affect the structure or function of the renal cortex. The histological picture of the samples after the intravenous injection of Au@Ac-12, Au@GKR, and Au@PEG was similar to that of the control sample. These findings confirm that the investigated Au@Ac-12, Au@GKR, and Au@PEG had no effect on the normal morphology and physiology of major organs.

-

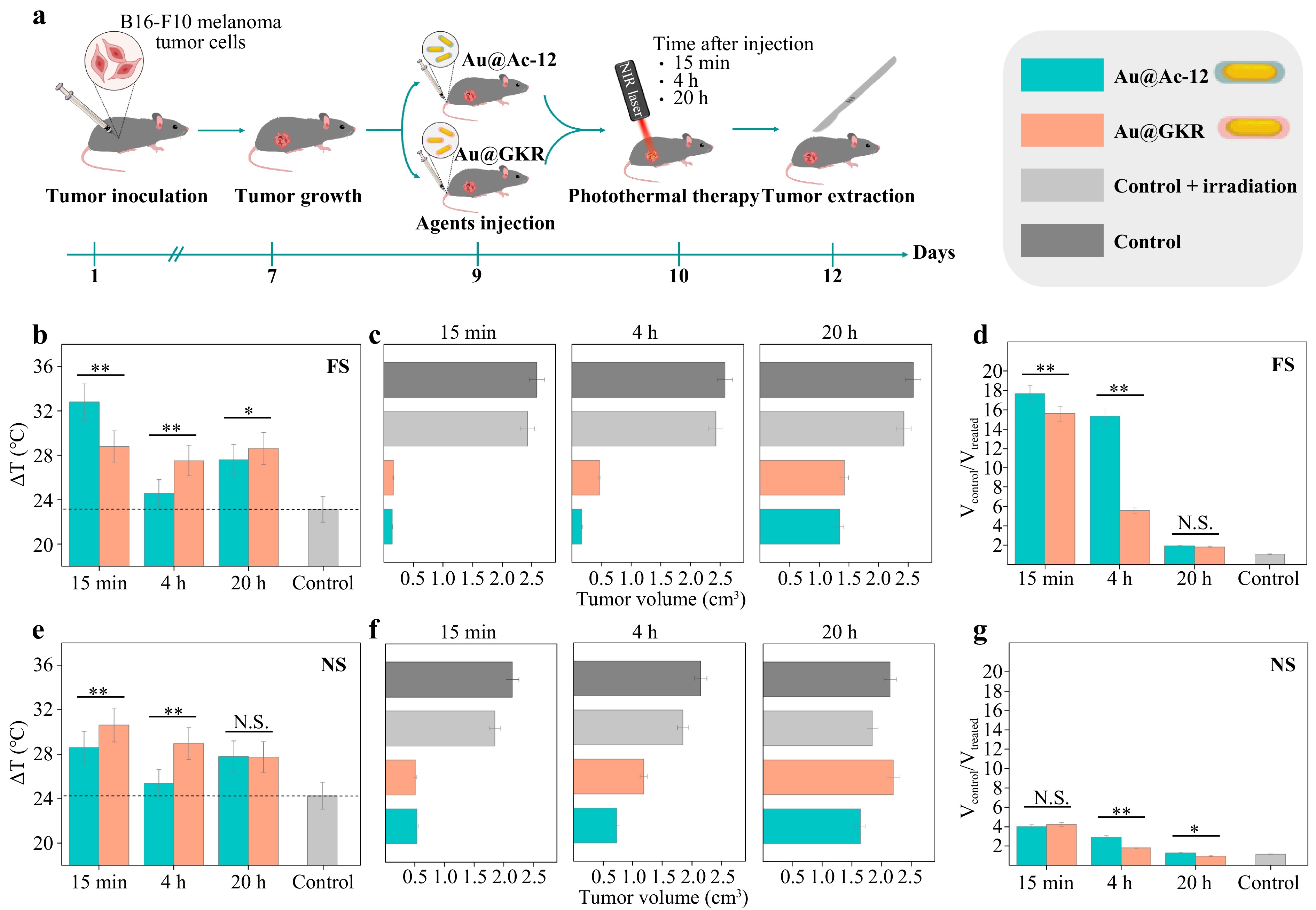

After verifying the targeting abilities of the peptide-coated Au NRs in vivo, we further studied the therapeutic capabilities of Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR under FS and NS laser irradiation. For this, B16-F10 tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice were divided into 11 groups (3 mice per group): (i) control with 0.9% NaCl, (ii) control with 0.9% NaCl and with FS laser irradiation, (iii) control with 0.9% NaCl and with NS laser irradiation, (iv) intravenously injected with Au@Ac-12 (100 μg NRs in 100 μL) without laser irradiation, (v) intravenously injected with Au@GKR (100 μg NRs in 100 μL) without laser irradiation, (vi) intravenously injected with Au@Ac-12 (100 μg NRs in 100 μL) with laser irradiation (15 min time point), (vii) intravenously injected with Au@Ac-12 (100 μg NRs in 100 μL) with laser irradiation (4 h time point), (viii) intravenously injected with Au@Ac-12 (100 μg NRs in 100 μL) with laser irradiation (20 h time point), (ix) intravenously injected with Au@GKR (100 μg NRs in 100 μL) with laser irradiation (15 min time point), (x) intravenously injected with Au@GKR (100 μg NRs in 100 μL) with laser irradiation (4 h time point), and (xi) intravenously injected with Au@GKR (100 μg NRs in 100 μL) with laser irradiation (20 h time point). Then, the mouse groups allocated for laser treatment were irradiated with either the FS laser (180 s; 1400 mW/cm2) or NS laser (180 s; 1400 mW/cm2) 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection (Fig. 7a, S16), simultaneously measuring the temperature with a thermal camera (Fig. 7b, e). Two days later, the mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were measured with a caliper (Fig. 7c, f, S17b, c). Once B16-F10 tumors grow with the same rate and achieve similar volume on the day before the treatment (Fig. S13), the tumor volume reduction rate was defined as a ratio between the control (Vcontrol) and treated (Vtreated) tumor volumes, was calculated and plotted versus time after the injection (Fig. 7d, g). Vcontrol is a mean volume of tumors in the group injected with 0.9% NaCl and not irradiated with a laser, while Vtreated is a mean volume of tumors from other groups treated with Au NRs, laser irradiation, or both. Control mice groups without injected Au NRs but irradiated either with FS or NS showed only negligible tumor inhibition. According to the obtained data, the temperature increase was more pronounced in the case of FS irradiation, especially for irradiation in the first minutes after the injection. This is in agreement with the previous observations (Fig. 1e-g). Notably, a slightly higher temperature was reached after irradiating Au@Ac-12-treated tumors with the FS laser, which can be explained by a higher accumulation of Au@Ac-12 in the tumor area confirmed with photoacoustic imaging (Fig. 6b, c, S14). As expected, a higher laser-induced heating resulted in a more intense tumor ablation in the case of the FS laser. Indeed, for the irradiation of tumor 15 min and 4 h after the injection, the tumor volume was significantly decreased, by 94% and 93%, respectively. This effect, however, diminishes in case of tumor irradiation 20 h post-injection (inhibited by 48%), which can be attributed to Au NRs washed from tumors, which corresponds to the photoacoustic imaging results. Generally, PTT with NS laser resulted in a lower tumor inhibition for all the animal groups, and, therefore, in a lower efficiency of PTT. For irradiation 15 min after the injection, the tumor growth was inhibited by 75%; after 4 h, by 66%; and after 20 h, by 23%. Thus, the tumor volume reduction rate drops with time of the irradiation after the injection more significantly for FS irradiation (Fig. 7d) compared to irradiation with NS pulses (Fig. 7g). These results are in agreement with the in vitro viability studies with B16-F10 cells (Fig. 5), which confirm that FS irradiation leads to a more intense heat generation and, therefore, a notably decreased cell viability. In the case of Au@GKR under FS laser irradiation, the percentage of tumor inhibition was 93%, 82%, and 45% 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection, respectively. Furthermore, for Au@GKR under NS laser irradiation, the tumor volumes were reduced by 76%, 45%, and 3% at 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection, respectively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Photothermal therapy using targeted Au NRs. a Scheme of therapy and tumor growth estimation. b Average temperature reached after 180 s of FS laser irradiation of tumors with Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection (the symbols ** and * indicate p < 0.005 and p < 0.05, respectively). c Measured tumor size for irradiation with FS laser 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection of Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR. d Tumor volume reduction rate for FS laser irradiation of tumors with Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection (the symbols ** and N.S. indicate p < 0.005 and no significant difference, respectively). e Average temperature reached after 180 s of NS laser irradiation of tumors with Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection (the symbols ** and N.S. indicate p < 0.005 and no significant difference, respectively). f Measured tumor size for irradiation with NS laser 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection of Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR. g Tumor volume reduction rate for NS laser irradiation of tumors with Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR 15 min, 4 h, and 20 h after the injection (the symbols **, *, and N.S. indicate p < 0.005, p < 0.05 and no significant difference, respectively). The graphic was prepared using modified art elements from Servier Medical Art, found at https://smart.servier.com, used under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

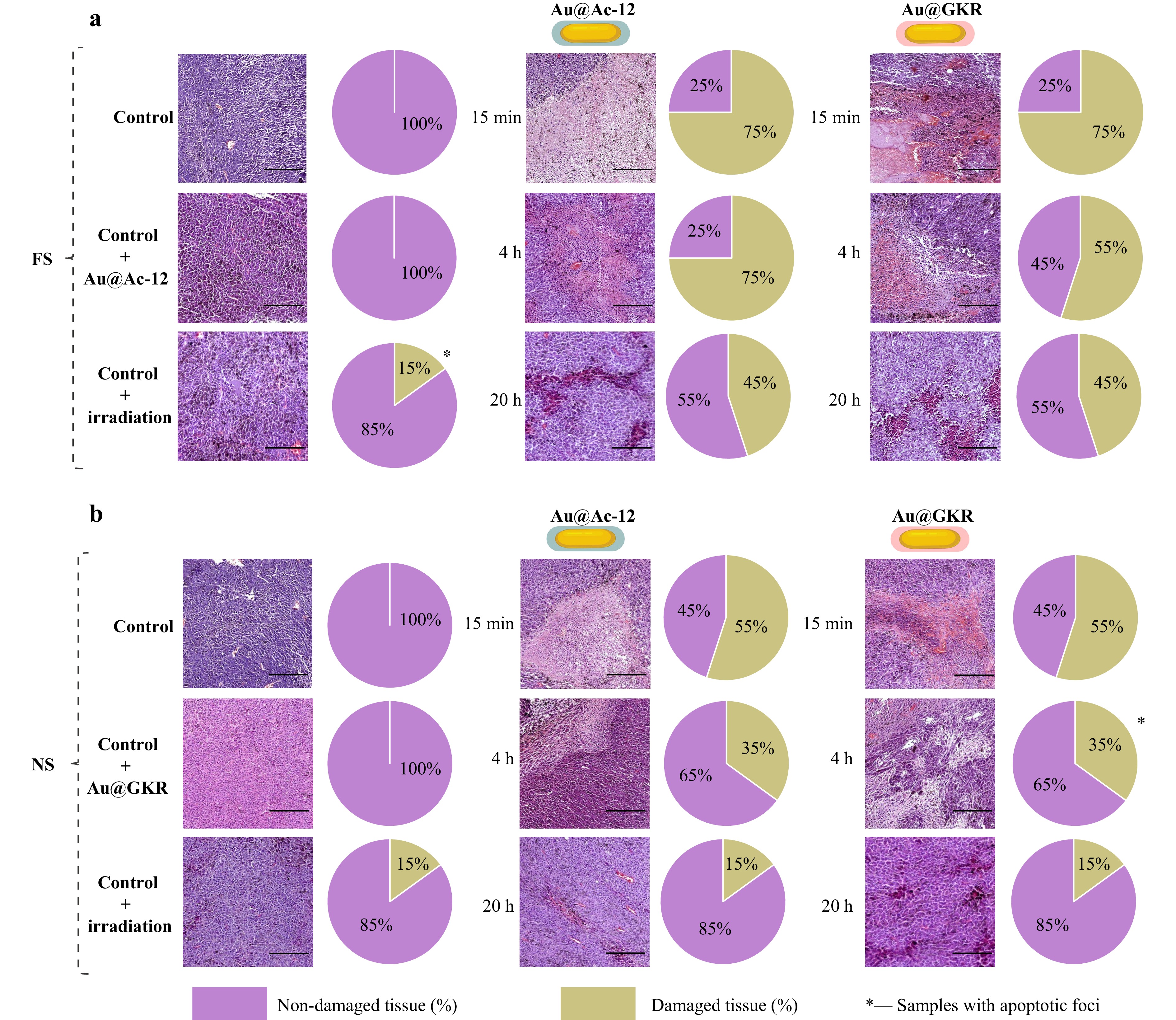

To reveal the impact of PTT on melanoma cells, we further conducted histological analysis of the tumors after treatment with Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR irradiated with either FS or NS pulses (Fig. 8). The tumor cells in the control group had a polymorphic and spindle structure, or polygonal shape. Multiple clusters of melanin granules were observed inside the cells, and cells at the mitosis stage were also detected. Vascularization was observed in the examined tumors. Invasive growth of tumor tissues and infiltration into the dermis and transversely striated skeletal muscle were noted. Remarkably, no signs of tissue damage were found in the non-treated and non-irradiated control samples. The control group with intravenous injection of either Au@Ac-12 or Au@GKR and no irradiation had similar histological patterns with no tissue damage detected, which is in agreement with previous findings (Fig. S15). As for the FS but not NS laser, it is worth noting that its irradiation, even without particles, can induce focal apoptosis in the tissue that is consistent with earlier studies (Fig. S18)59,60. Next, we separately considered the groups depending on the type of laser radiation. In most samples, coagulative necrosis was observed, which is typical under hyperthermic exposure. In the case of FS laser irradiation, the number of actively dividing cells decreased, and melanin granules were more accumulated in the intercellular space due to the loss of cell structure integrity as a result of tissue necrotization. The volume and distribution of the necrotic areas vary depending on the time of irradiation after the nanoparticle injection. For instance, for irradiation 15 min after the injection, necrotic areas with a volume of 70%−80% were observed in the case of Au@Ac-12 and Au@GKR. For the 4 h irradiation, the volume of damaged tissue decreased to 50%−60% for Au@GKR, but remained at the same level for Au@Ac-12, which was in agreement with the PTT data (Fig. 7d). It is important to note that besides necrotic areas, multiple apoptotic foci appeared in the Au@GKR-treated group irradiated with NS laser after 4 hours post-injection (Fig. 8b), which is likely due to lower accumulation of nanoparticles in the tumors compared to Ac-12 and to the milder hyperthermia induced by the NS laser compared to the FS laser. For irradiation 20 h after the injection, the percentage of damaged tissue was 40%−50% for both Au NR types. In the case of NS irradiation, tissue damage was most pronounced at 15 min (50%−60%) and 4 h (30%−40%). For irradiation at 20 h, the histological picture was partially similar to the intact tissues of the control groups without irradiation, in which small areas of tissue damage were determined. The volume of damaged tissue was estimated using a visual method, considering the total area of damaged tissue normalized on the whole tumor tissue in the histological sample. Apoptotic and necrotic cells were distinguished by morphology evaluated histologically at high magnification.

Fig. 8 H&E stained histological images of tumors after targeted PTT with corresponding diagrams showing percentage of non-damaged/damaged tissues: intact tumor; tumor with intravenously injected Au@Ac-12 without irradiation; tumor irradiated with laser; tumor with intravenously injected Au@Ac-12 irradiated with laser after 15 min; tumor with intravenously injected Au@Ac-12 irradiated with laser after 4 h; tumor with intravenously injected Au@Ac-12 irradiated with laser after 20 h; tumor with intravenously injected Au@GKR irradiated with laser after 15 min; tumor with intravenously injected Au@GKR irradiated with laser after 4 h; tumor with intravenously injected Au@GKR irradiated with laser after 20 h, a FS-pulsed irradiation mode, b NS-pulsed irradiation mode. Scale bar corresponds to 50 µm.

The obtained results clearly show that the NS laser is less efficient for photothermal therapy (PTT) using Au NRs, as evidenced by a lower inhibition of tumor growth. Despite the lower temperatures in tissues achieved with NRs under NS laser irradiation, the predominant linear absorption characteristic of NS laser modes leads to a considerable photodamage61. This phenomenon results from heating of NRs and subsequent heat diffusion, causing collateral thermal damage to neighboring tissues, as observed in our study62.

Conversely, in the case of FS laser pulses, where the pulse energy is concentrated over a short period of time (pulse duration), an increased photon flux can trigger nonlinear multiphoton absorption processes. These processes involve the creation of a free electron plasma confined within a focal volume, reducing the irradiation volume and thereby minimizing damage to surrounding tissues63. For short laser pulses (FS), laser energy is predominantly absorbed by NRs, and the target cell damage occurs primarily due to heat release from plasmonic NRs64,65. Moreover, at low repetition rates (<MHz, in our case, kHz) and increased intensities, water evaporation can generate cavitation bubbles around the particles, further contributing to the target cell damage66.

Importantly, following the interaction of Au NRs with biological entities such as cells or tissues, they tend to aggregate on the cell surface or within cells67 (Fig. 3e-g). Closely located particles enhance the near field, and the interaction between the Au NRs is promoted through scattered waves, leading to the formation of “hot spots” via plasmon coupling. This enhanced field induces temperature elevation, enhancing the cell and tissue damage.

-

Phototherapy efficiency enhancement involves the use of effective thermal agents that excel in light-to-heat conversion and possess active targeting capabilities. To this end, we designed targeting plasmonic nanoparticles (Au NRs) modified with two types of peptides: one that closely mimics the αMSH sequence (Ac-12) and the other that targets MC1Rs and includes additional linkers for enhanced conjugation (GKR). Both theoretical and experimental assessments of the heating abilities of obtained plasmonic NRs reveal more intense heat generation under the FS-pulsed regime compared with NS, due to the relaxation rates of the electron and phonon temperatures that dissipate in the surrounding water. Indeed, equivalent laser power densities result in more efficient Au NRs heating under the FS-pulsed laser regime because of the rapid cooling of NRs through the dissipation of heat into water (>1 ns), which makes the NS-pulse too slow to achieve maximal temperature increase.

Photoacoustic imaging of intravenously injected peptide-coated Au NPs revealed higher tumor accumulation efficiency for Au NPs coated with peptide (Ac-12), which has the highest affinity to MC1R, overexpressed on the melanoma cell surface. This was also confirmed by a slightly higher reached temperature during photothermal therapy. Overall, inhibition of tumor growth was more pronounced in the case of FS-pulsed laser irradiation, proving the better applicability of FS laser for tumor ablation applications. Indeed, in the case of FS, increased photon flux leads to nonlinear absorption processes that reduce the irradiation volume and damage the surrounding tissues, which is in agreement with our theoretical investigations. In turn, the linear absorption characteristics of NS-pulsed laser modes result in considerable heat diffusion to the surroundings and consequent adverse effects. This systematic rigorous study underlines that a high binding affinity between the ligand and targeted tissues, as well as the right choice of irradiation source with sufficient parameters, is essential for improved PTT outcomes.

-

The chemicals used in this study were purchased from commercial companies and used without further purification. The detailed information about the materials used is provided in the Supporting Information.

-

Gold (Au) NRs were obtained in a binary surfactant mixture using a seed-mediated growth approach, as reported by Ye et al25. The surface of the obtained Au NRs was further covered with SH-PEG-COOH using a ligand exchange procedure. The size and shape of the developed Au NRs were confirmed using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (TEM) Zeiss Libra 200F (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The obtained Au NRs were then covalently modified with two αMSH-like peptides (Ac-12 and GKR). The successful modification was confirmed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy using a TENSOR II FTIR Spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Germany). The colloidal stability of the coated Au NRs was analyzed using a dynamic light scattering (DLS) approach with a Photocor Complex (Photocor, Russia). The details are presented in the Supporting Information.

-

Assessment of the cellular uptake was performed using B16-F10 melanoma cells. Cy5-labeled Au@PEG, Au@Ac-12, and Au@GKR were added to B16-F10 melanoma cells at a concentration of 150 μg/mL and incubated for 24 h. The uptake of Au NRs by B16-F10 cells was analyzed using CLSM imaging to visualize fluorescently labeled Au NRs. The details are presented in the Supporting Information.

-

Healthy C57BL/6 mice aged 6−8 weeks and weighing 18−22 g were purchased from Rappolovo, St. Petersburg, Russia. To model melanoma, B16-F10 cells were cultured in α-minimum Eagle’s essential medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone, USA) and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Afterward, B16-F10 cells were injected into the mice’ legs. On the 7th day after the tumor inoculation, mice were randomly divided into experimental groups for further in vivo studies. The details are given in the Supporting Information.

-

Photoacoustic imaging was used to investigate the effectiveness of targeting. The tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with Au@PEG, Au@Ac-12, and Au@GKR on the 7th day after the tumor establishment and used for photoacoustic signal detection. The signal from the modified Au NRs inside the tumor was obtained using a TriTom (PhotoSound Technologies, Inc., USA) imaging platform with a PhotoSonus (Ekspla, Lithuania) pulsed laser (wavelength 1064 nm, pulse energy 80 mJ). Immediately after the measurement, the mice were euthanized, and the tumor and major organs (the liver, lungs, kidney, spleen, and heart) were removed for subsequent histological examination of the tissues for toxic effects.The details are given in the Supporting Information.

-

Two types of NIR lasers were used to perform PTT: FS (1030 nm, 1400 mW/cm2) and NS (1064 nm, 1400 mW/cm2) lasers. The tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with targeted Au NRs on the 7th day after the tumor establishment and irradiated for 3 min. During the experiment, the temperature of the tumor was monitored using an IR thermal imaging camera, FLIR Titanium 520 M. The mice were euthanized on the 2nd day after therapy, tumors were removed, and their size was measured using calipers. The detailed information is provided in the Supporting Information.

-

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Shapiro-Wilk’s normality test, ANOVA, and Tukey’s HSD test were employed to determine the significance of disparities among numerous experimental datasets.

-

Part of this work related to the synthesis of nanomaterials by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 24-75-10006). Part of this work related to the biological experiments was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 21-75-30020). Part of this work related to the characterization of nanomaterials was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russia (grant number 075-15-2021-1349). The authors acknowledge the Clover Program and the Priority 2030 Federal Academic Leadership Program. The authors acknowledge Lidia Pogorelskaya for the proof-reading of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the Nanotechnology Centre of SPbSU for electron microscopy studies. The work was partially performed at the ITMO Core Facility Center “Nanotechnologies”.

A comparative study of plasmonic nanoparticles for targeted photothermal therapy of melanoma tumors using various irradiation modes

- Light: Advanced Manufacturing , Article number: (2025)

- Received: 12 June 2024

- Revised: 12 November 2024

- Accepted: 13 November 2024 Published online: 11 March 2025

doi: https://doi.org/10.37188/lam.2025.005

Abstract: Melanoma, a highly malignant and complex form of cancer, has increased in global incidence, with a growing number of new cases annually. Active targeting strategies, such as leveraging the α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (αMSH) and its interaction with the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) overexpressed in melanoma cells, enhance the concentration of therapeutic agents at tumor sites. For instance, targeted delivery of plasmonic light-sensitive agents and precise hyperthermia management provide an effective, minimally invasive treatment for tumors. In this work, we present a comparative study on targeted photothermal therapy (PTT) using plasmonic gold nanorods (Au NRs) as a robust and safe nanotool to reveal how key treatment parameters affect therapy outcomes. Using an animal model (B16-F10) of melanoma tumors, we compare the targeting abilities of Au NRs modified with two different MC1R agonists, either closely mimicking the αMSH sequence or providing a superior functionalization extent of Au NRs (4.5% (w/w) versus 1.8% (w/w)), revealing 1.6 times better intratumoral localization. Following theoretical and experimental assessments of the heating capabilities of the developed Au NRs under laser irradiation in either the femtosecond (FS)- or nanosecond (NS)- pulsed regime, we perform targeted PTT employing two types of peptide-modified Au NRs and compare therapeutic outcomes revealing the most appropriate PTT conditions. Our investigation reveals greater heat release from Au NRs under irradiation with FS laser, due to the relaxation rates of the electron and phonon temperatures dissipating in the surrounding, which correlates with a more pronounced 17.6 times inhibition of tumor growth when using FS-pulsed regime.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article′s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article′s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: